(Thanks to Carl Vellotti for talking through some of these ideas)

A team builds a feature to close a big deal. The benefit is immediate. The big question is whether it will offer long-term benefits beyond immediate gratification. Taken in isolation, the feature isn’t worth the effort and the added complexity to the product.

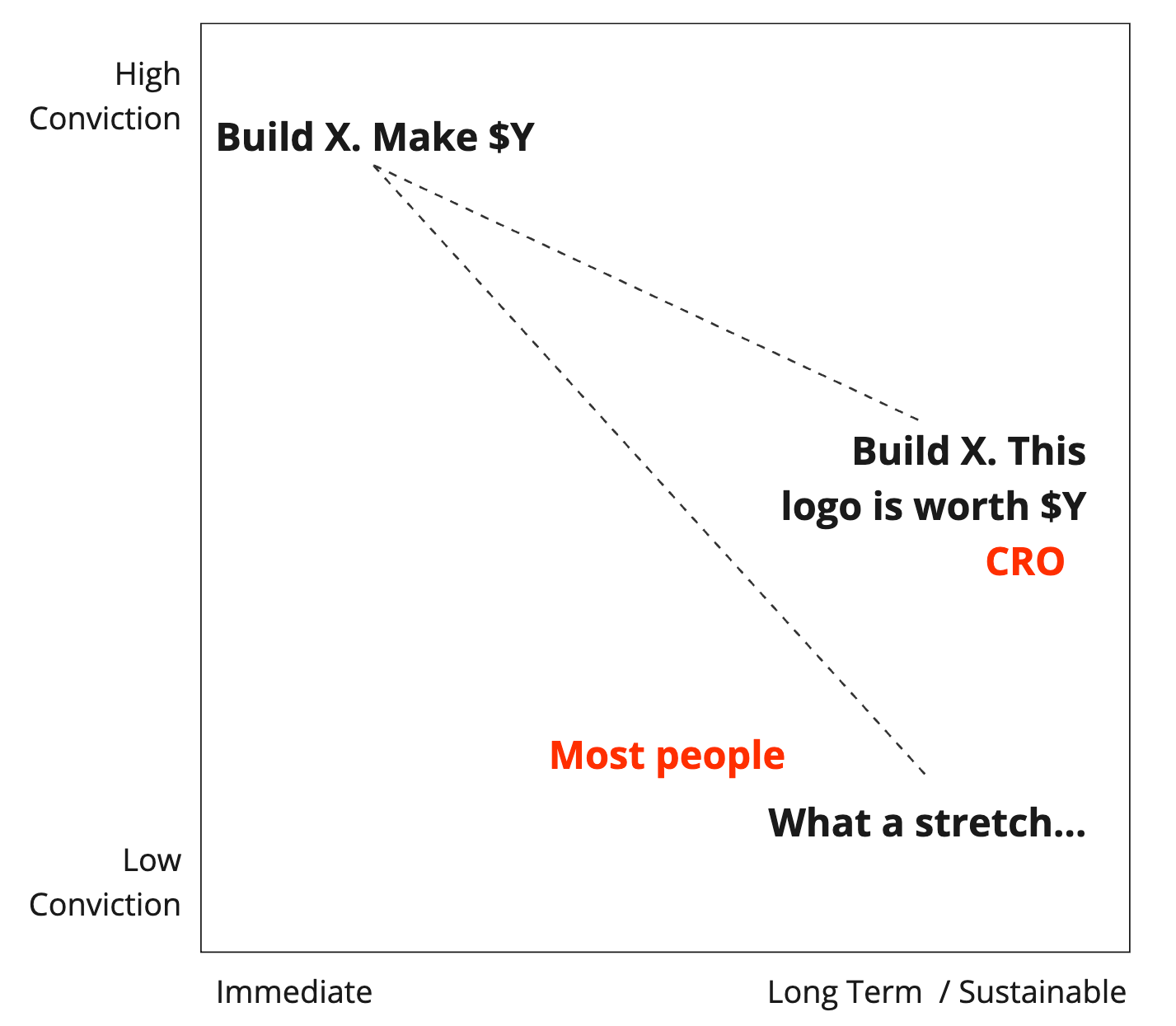

The CRO tosses in an assumption:

This logo will be a HUGE benefit for us. Not only will closing this deal help us make the quarter—but it will ALSO pay off huge dividends in the future when everyone sees we got Acme as a customer. They’ve given us logo rights!

Most people at the company have lower levels of convictions. Compared to the high conviction of “Build X. Make $Y,” the idea of “Build X. This logo is worth $Y” feels like a big stretch. Past forecasts of “huge dividends” have yet to materialize.

Let’s diagram the situation like this:

OK. A non-work example.

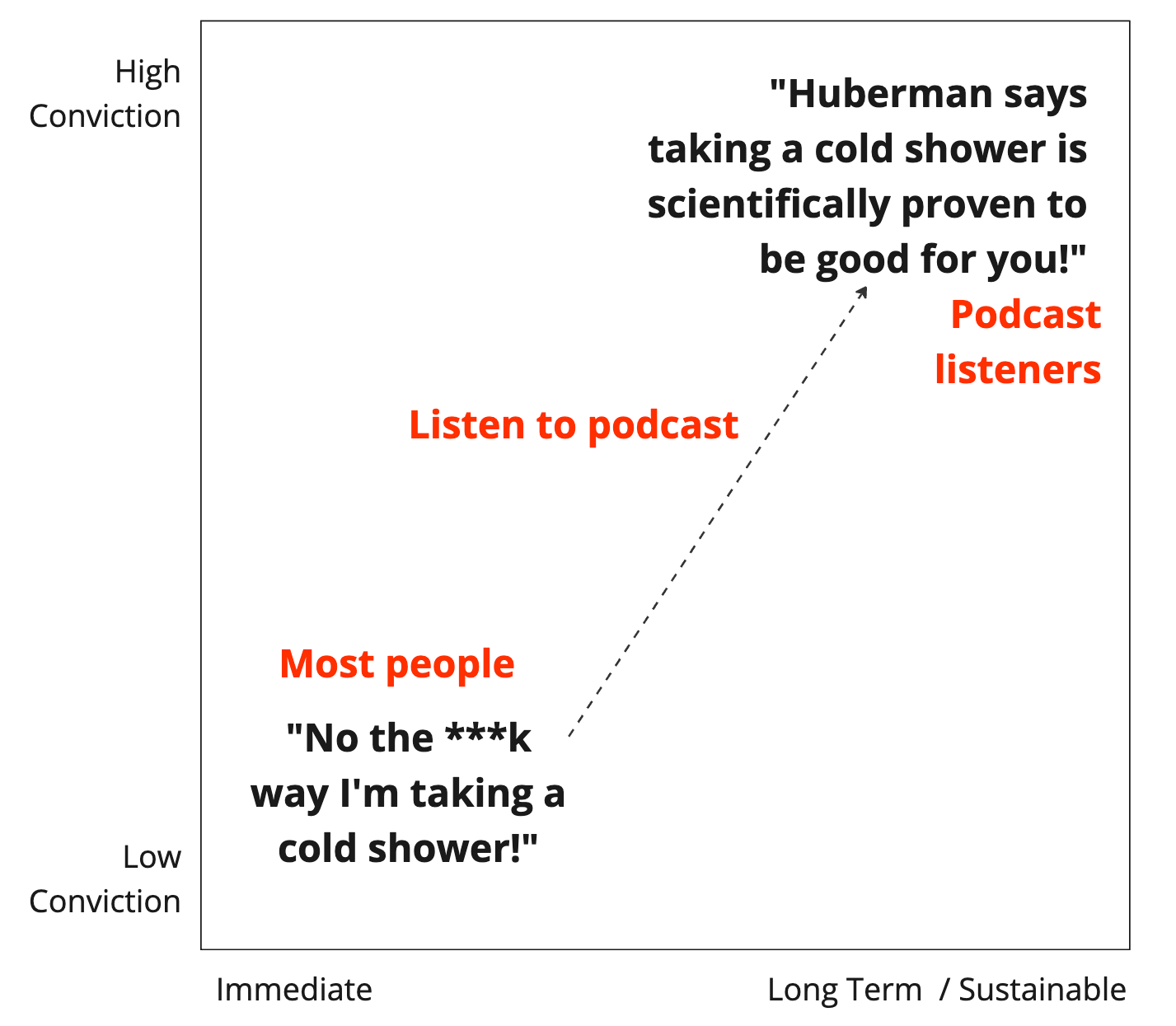

Dr. Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist, and professor at Stanford University, has popularized the use of cold water exposure for its numerous health benefits, especially for improving sleep quality, reducing stress, and enhancing mood. He is very persuasive—citing scientific evidence, trying things on himself, etc.

It looks like this:

Huberman persuades people to do things they find very uncomfortable because he has created a “model” that inspires high conviction by combining scientific evidence and a good podcast. Religions (and cults) are also good at making people do uncomfortable things because they have good models.

OK. What does this have to do with goal cascades?

Imagine a “normal” annual or biannual planning process. Everyone is throwing out pet ideas! Politics everywhere. If something can generate immediate $ it is good—you might as well throw darts at the other stuff. It is like an elaborate game of Tetris designed to sap the lifeblood out of even the hardiest product manager. By December (or June), people just want it over. No one has any energy left to push back. But lo and behold, the plan emerges.

How much conviction would you expect to emerge from that approach? Not much. Yet this is the status quo in many companies hence why conviction falls apart by June.

Imagine a “normal” annual “cascading” OKR process that starts with goals (not projects with goals tacked on to them). The highest level goals are financial (mixed with a couple of qualitative goals that are agonizingly generic—, but that fit neatly on a slide). The team starts an elaborate process of “to hit that goal, what goal should we hit?” Down it goes—down the cascade. Each step involves assumptions:

How much conviction would you expect to emerge from that approach?

It might be fine for immediate outcomes (transactional games) or long-term outcomes (with high conviction). Maybe the company has proven that if they can get X visits to their website, they will get Y leads and end up with Z customers. And perhaps they have also proven that they can keep customers and increase ARR. In that case, the conviction would be high.

If all of that is in place, the “cascade” may be acceptable—even if the goals at the “bottom” feel like taking a cold shower or building feature X. The same would hold in our first example if you had data on the impact of marquee logos. High conviction in your models is terrific if you can get it.

Most OKR goal cascades don’t fit the bill.

I’ve recently realized my problem with cascades. They tend to have low conviction.

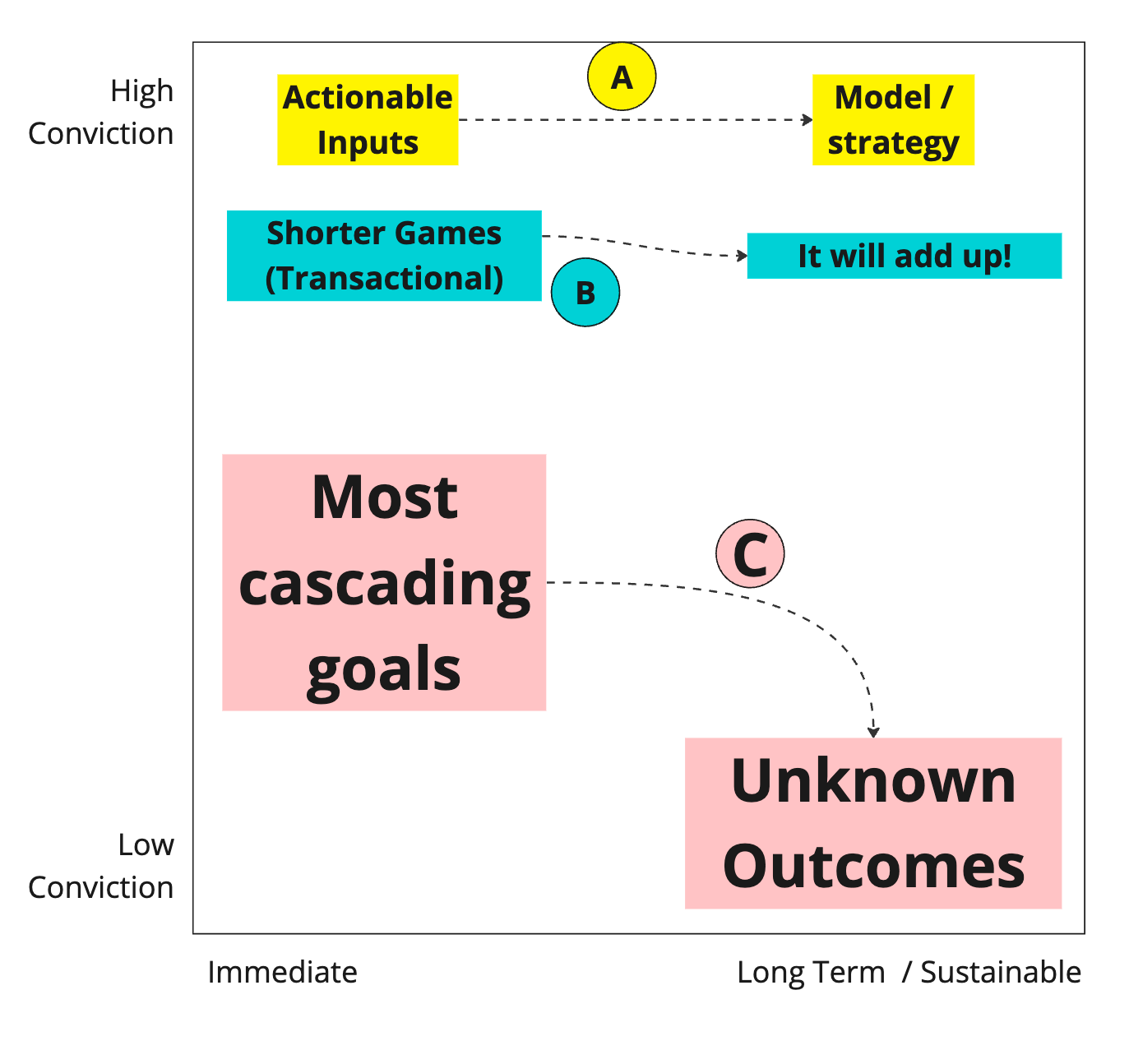

We can have:

Transactional, shorter-term games.

Longer games that require actionable inputs linked to a high conviction model (or strategy, perhaps strategies are “models” of beliefs and assumptions).

Cascading goals linking non-actionable goals to unknown sustainable outcomes where we have low conviction.

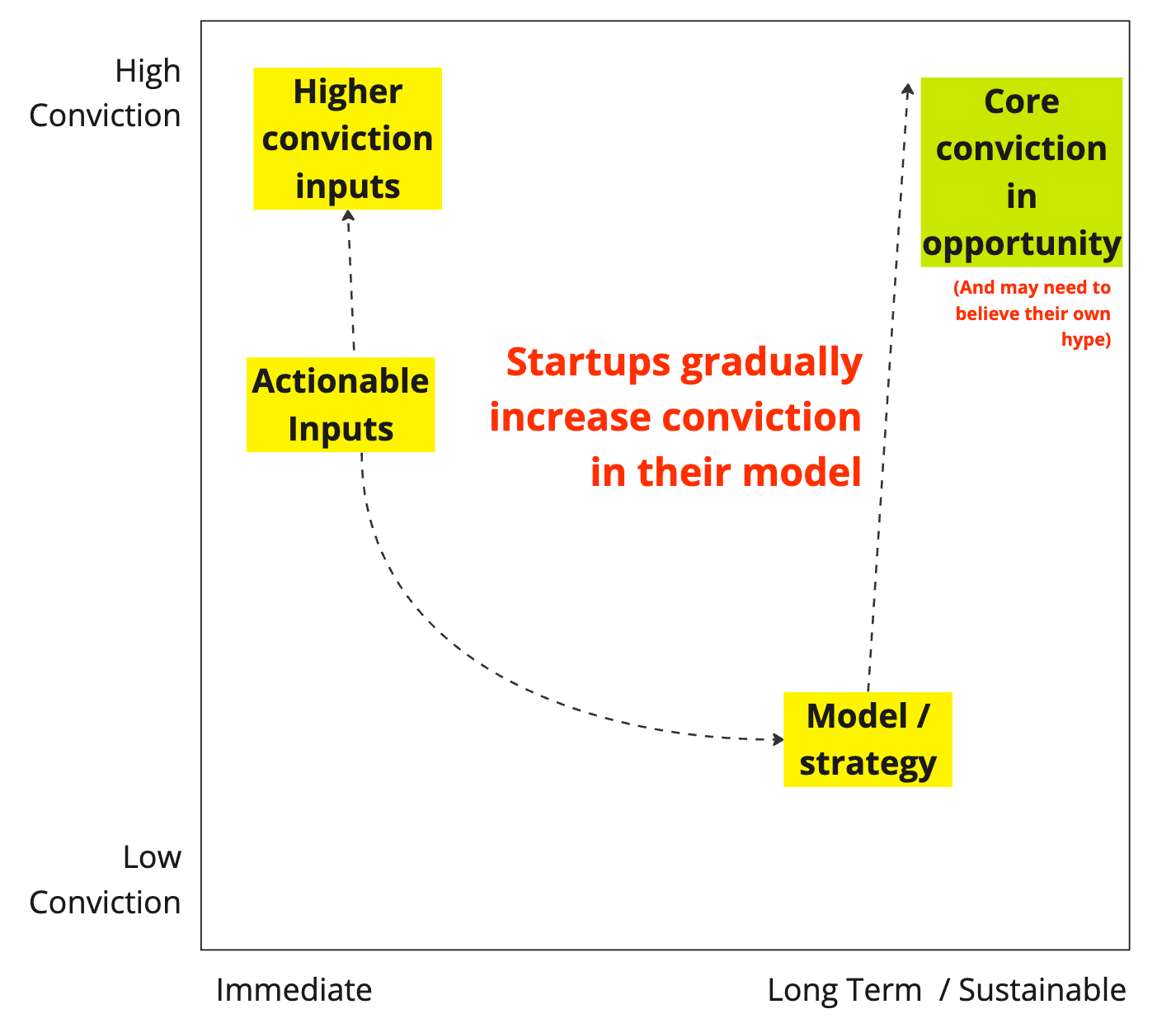

There’s almost no way a company will develop a high conviction model as part of a reactive, single annual planning cycle unless they are a very transactional business with a tight connection between short-term actions and $. Building conviction is a long-term and continuous effort in most cases (in some cases spanning jobs and companies).

I realized recently that all of my work on the North Star Playbook (see this resource library with tons of templates, videos, a book, etc.) was about developing a high-conviction model that could serve as a springboard for aligned autonomy (actionable inputs) that link to sustainable outcomes through a North Star Metric.

To tell the difference between a harmful cascade and an effective tree/graph, ask if it is a high-conviction model. If people shrug—wondering if their actionable goals will impact sustainable, long-term growth—you probably have a low conviction model and a harmful cascade. Or you are a startup finding your way:

(Parting thought…what is the equivalent of Huberman’s cold shower at your company? What do you have high conviction about, that from the outside may seem irrational?)

John, could you point to resources abt the definition of actionable inputs?

I owned a copy of art of action by Stephen bungay so aligned autonomy is familiar to me

Less so actionable inputs

I have googled but nothing good shows up

Best I have found is these two

https://www.managementstudyguide.com/ensuring-that-inputs-are-recorded-at-actionable-level.htm

https://www.managementstudyguide.com/recording-inputs-at-actionable-level.htm

Really creative framing of connecting the dots from Lagging Business Impact Goals ($) to Leading & Lagging Outcomes via a North Star metric.

I know I’m in the minority on this, but personally, I believe you need to start with *strategy*, then set metric goals (Leading to Lagging) to measure the effectiveness of that strategy.