TBM 17/52: The Problem With Problems

People often distinguish between problem solving and problem definition.

The product manager’s responsibility is to define the problem to be solved. The team's responsibility is to solve the problem.

There are issues with this. I don’t think the distinction is as helpful as we think.

No problem exists on an island.

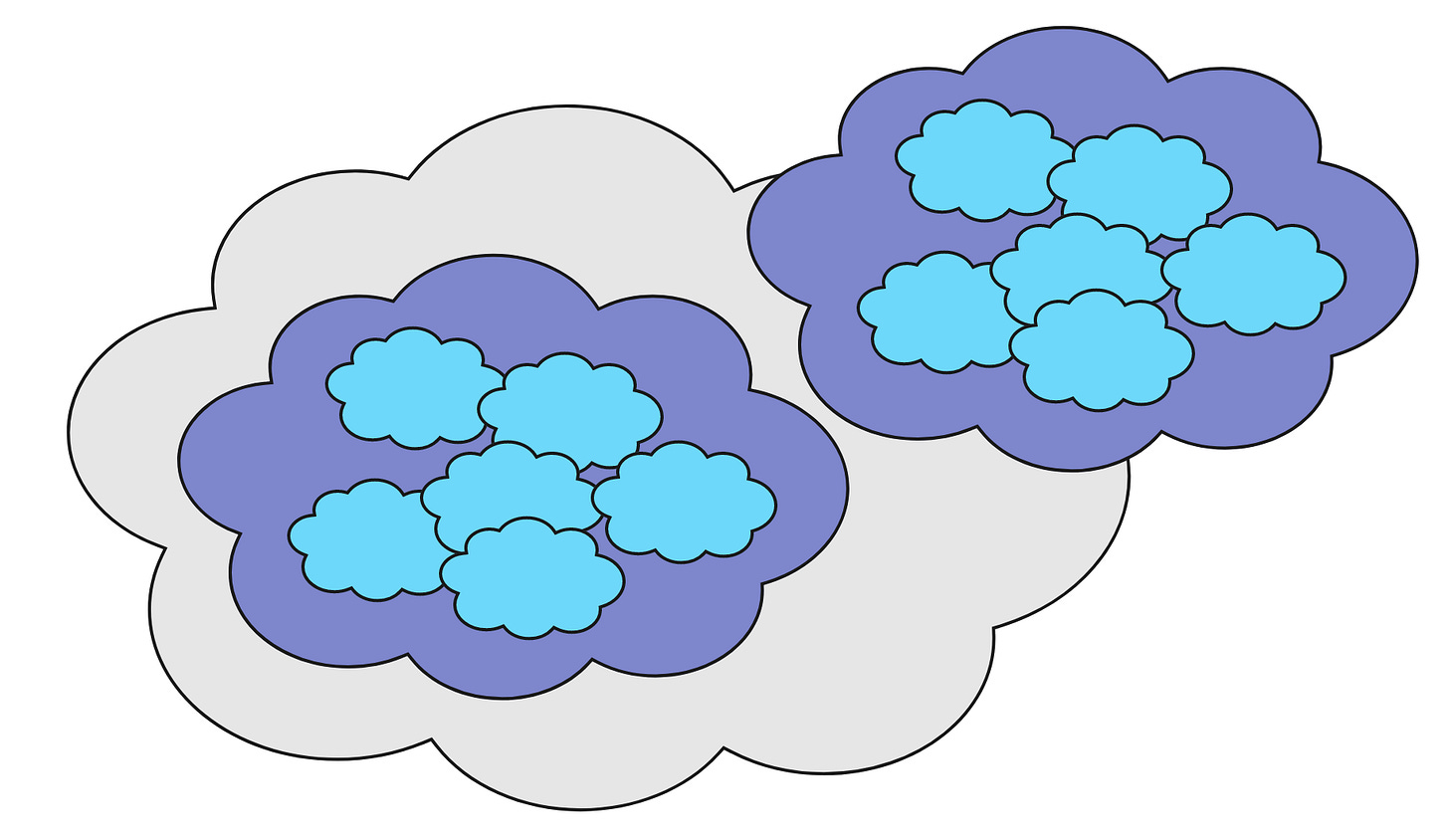

Every problem is a nested solution to a higher level problem. Every problem is a collection of nested problems.

For example “our enterprise deals take too long to close” assumes that accelerating enterprise deals will have some sort of positive business impact, or will solve a higher level problem. Going up one level we might discover “it costs us too much to land an enterprise customer” or “long deal cycles are one cause of losing deals”. Up another level…revenue growth and acquisition costs.

There are likely other ways to have the same impact. We can increase deal volume and average contract size, for example. Accelerating enterprise deals is ONE potential solution to the higher level problem. Which itself is a solution to an even higher level problem. On and on.

Companies, themselves, are solutions to higher level problems.

Perspective and experience matters.

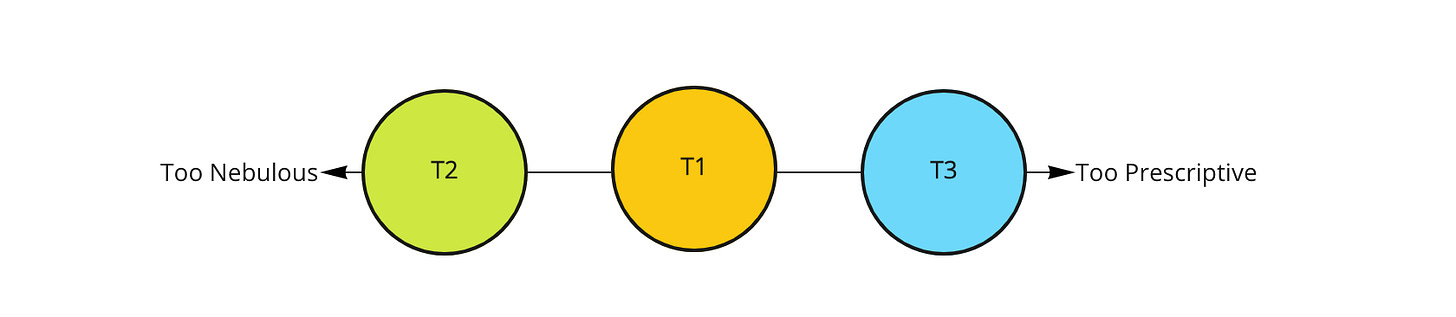

This doesn’t make “our enterprise deals take too long to close” a bad problem statement. For some teams that level of resolution is perfect. It leaves a lot of room for creative problem solving AND problem exploration and definition.

Other teams would need help. They’d need the problem “broken down” into defined sub-problems. An example of a sub-problem might be “it takes us a long time to identify all of the key influencers”.

Still other teams would find that original problem statement unsatisfactory, overly opinionated, and solution-like. What kinds of enterprise deals? Why not other deals that are easier to close? What if accelerating the deals increases the chance of churn?

Your most passionate problem solvers AND definers are always pushing the limits. You want these people on your team, but their insistence to keep digging and questioning can be draining.

So…the line between problem and solution is fuzzy, and contextual, and subjective. These challenges don’t magically go away if we talk about opportunities vs. solutions, or input vs. output metrics, or outcomes vs. outputs, or driver vs. goal metrics. The same dynamics apply.

It’s always a big web of assumptions and hypotheses. It’s a mess.

Not all problems are worth solving. Not all problems are solvable.

Every problem has two adjacent “problems”, and that is 1) the puzzle of figuring out if the original problem is worth solving, and 2) whether the original problem is solvable given certain constraints.

Some product managers, designers, and engineers are great at defining the problem. “Here is my copious research about the nature of the customer problem! It is real! It exists!” But not as good at figuring out whether the problem is worth solving now. Is this the highest leverage thing we could be doing? What is the opportunity?

An opportunity is a problem worth solving with a feasible path to making some progress (even if that path is all about learning whether the problem actually exists). So the problem isn’t just the problem itself. You have problems like viability, feasibility, opportunity, leverage, etc.

Problem definition is negotiation.

Organizations put a lot of pressure on people to “define problems”.

In this sense, problem definition is political. It’s a negotiation. If you–person A over there–can perfectly define the problem, then you–person B over there–are on the hook to solve it. If we discover that the problem wasn’t defined well, we will blame person A. If the solution doesn’t work well, we will blame person B. Deniable culpability.

The same thing happens with “defining OKRs”, or “defining goals”. And anywhere that happens, you run the risk of people losing sight of the ultimate goal because they’re optimizing for internal negotiation.

We fall in love with problems as easily as we fall in love with solutions.

Putting pressure on people to “clearly define the problem” can bias people against asking the right questions. We fall in love with problems as easily as we fall in love with solutions (especially since most problems are also solutions). Which causes us to prematurely converge on a definition of the problem, and inflate the value of solving the problem. If we only tackle problems that can be perfectly defined, then we will only try to solve commodity problems (since commodity problems are underpinned by available information).

What a puzzle! Do we linger on trying to eke out the last remaining 10% of problem uncertainty before taking action? Or take action, and hope to learn more about the problem that way? How many “totally nebulous but potentially very valuable” bets should we make? The upside might be amazing. Or might not. How do we make it safe to not know?

So watch out.

So what can you do about all this? What’s the point?

Be aware that the problem vs. solution dichotomy isn’t all that clear. It sounds good. But there are many cases where it isn’t very helpful.

Problem wrangling involves exploration, definition, appraising, untangling, tangling, and solving on repeat. Avoid putting up walls, or stereotyping people. Avoid processes that encourage binary thinking.

Sometimes, solutions help us understand problems! Don’t dogmatically avoid solutions. They help us make sense of things.

Consider the opportunity framing instead of problem framing. “Problem” invites the attitude of “it must be defined”. Has it been solved? Yes? No? Credit! No Credit! We don’t want that. We’re always on a journey of surfing opportunities.

Context and connectivity. Whenever possible, “map” opportunities to support shared understanding. Embrace the mess. Use whatever tree/mapping approach you enjoy using.

Hope this was interesting!

Wondering if even the most hardcore “problem-first” of us aren’t able to be so only because we already had a solution <> problem dialog, maybe unconsciously

The problems and related opportunity for a solution +outcome for all parties involved aligns depending on which level of abstraction one is looking at the problem from - individual, technological, societal, process, supply chain, economic, moral, ethical, etc., more often than not the solution ends up being over indexed for the solver's (company, decision making individual, etc) needs and wants not for those that are actually facing the problems.