TBM 56/52: The NPS Effect

The end of TBM year three. Wow! 156 weeks. 190 posts. Just hit the 3,000,000th view (more importantly, people seem to come back). Thank you so much for your support—all the best for 2023. I do have some news on the career-front which will hopefully take my writing to new (but different) places.

This post is not actually about NPS. Instead, I use NPS to describe the NPS Effect—a dynamic that impacts everything in business and life. You almost certainly grapple with the NPS Effect in your day-to-day work.

We will not dig into the issues with NPS to understand the effect. Those are described well elsewhere. Instead, we will examine the social dynamics and biases surrounding NPS.

Let’s start with ten key NPS observations.

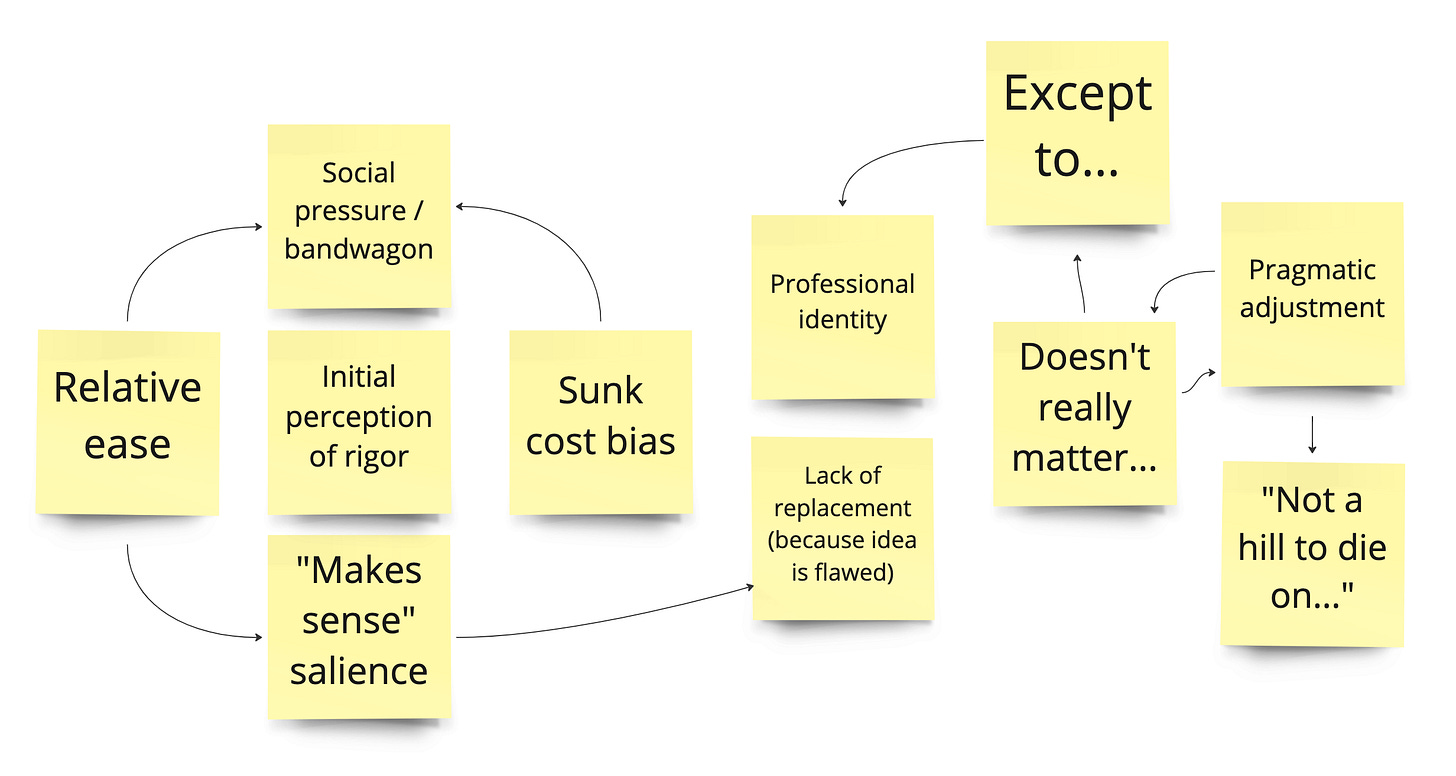

It is relatively easy to collect the data for NPS. There are various documented issues with the data you're collecting, but the sheer mechanics are within reach of almost any company.

NPS lets you compare your NPS with the NPS of similar companies. "How do we stack up against our competitors?" is one of the age-old questions in business and life. Social comparison bias is potent.

Enough companies are using NPS to trigger the bandwagon effect. "Why should we be the exception here?" is a common refrain.

A personal recommendation IS a powerful form of endorsement. Most humans value the recommendations they receive from friends and also pride themselves on giving good recommendations. Because of that salience, people intuitively get NPS. "I get the issues," explained an executive once, "but it is asking a super straightforward question—that everyone cares about!"

The eleven-option scale and the calculation (boiling down eleven options into three buckets) has a strong "more is better" and "see it is rigorous" vibe. More options feel more comprehensive and more likely to let someone express their true, nuanced feelings. 10-point scales are popular ("on a scale of one to ten"). So despite the research pointing to the issues with these scales, they feel better somehow.

Imagine a company using NPS with a couple of years of historical data. That's a substantial perceived investment to walk away from. First, you would need to admit the data was flawed in some way—which is especially hard given the salience mentioned above. No one wants to be someone who doesn't care about customer satisfaction. Second, tracking anything over multiple years is compelling ("there has to be some value in the trends, right?"). Third, there would be a lot of pressure to find a replacement with similar properties/characteristics (which is difficult).

Very concretely, NPS becomes part of the job description of some people in every company that uses it. Job descriptions have an uncanny way of seeping into our professional identity.

Many companies have a "and we improved our NPS" story—an additional layer of the sunk-cost fallacy. You are the executive that presided over the improvement. It was a great story—you went from being below average for your industry to being a standout performer. "It worked, right?"

To the point about a replacement: any self-respecting analyst, researcher, or statistician will tell you that there are no drop-in replacement options with the same characteristics. There are tried-and-true techniques to measure many things, but most tried-and-true methods are more focused. The whole idea is broken. Any pushback and fretting have the net effect of leaving executives frustrated with the "it depends" crowd. This brings us to:

For many data folks, NPS becomes one of those "that's not a hill I am going to die on" things. Of all the areas they can spend energy on, trying to talk their organization out of a popularly used metric is not a great card to play. They correctly choose the option of influencing in other ways. So NPS persists.

Together these combine into what I think of as the NPS Effect. The NPS Effect explains why less-than-optimal things can persist in business for a long time—even when a good % of the team wouldn't recommend those things to a friend.

Aside, what is the NPS of NPS?

Let's consider some of the themes above: perceived ease, salience, social pressure, competitive pressure, sunk-cost bias, professional identity, pride, the allure of simplicity, inertia, perceived rigor-meets-simplicity, and lack of "equal" options. Any of those in isolation is powerful. Together, it is a potent soup!

But the NPS Effect is all that and something more. Pavel Samsonov puts it well:

If it is meaningless, it is very easy to integrate into any process!

I would extend that through a thought experiment.

Imagine that NPS was highly actionable. Imagine everyone bought into what it was intended to measure and what it meant. Imagine your company's analysts and data experts desperately wanting to spend their time digging into the data. Instead of the typical detachment, fatigue, and resignation I observe in organizations related to NPS…all out passion.

Well, imagine how many PROBLEMS that would cause! Goodness. People would start taking it super seriously. Suddenly it would be a hill experts die on.

The better thing is more challenging to convince others that it's better. So everything conspires to go with the mediocre solution.

We are surrounded by stuff like this in the workplace—not overtly objectionable, but also not very helpful.

Counterintuitively, we pick things like NPS because of their failings, not despite them. And then, for various reasons, they become more and more entrenched. The entrenchment mixed with “neutral” appeal makes people less willing to make a stand and more willing just to let it ride. Rational people get pragmatic, and make the best of it (“well, the qualitative stuff IS helpful…”).

The cycle repeats.

Except maybe next year :)

Which will go to 11. Or 10, if you start at 0.

Happy New Years!

It is painful how accurate this is. I'm thinking: eNPS, 9-box, story points...

Oooh do you think OKRs are going through a similar pattern? I’ve seen a bunch of beef about them online recently and it rhymes with the NPS beef.