TBM 406: Seeing Everything, Understanding Nothing (The Context Trap)

AI is supercharging legacy leadership assumptions about context and control. In AI discourse, “context” is increasingly framed as the new source of truth. It’s a familiar and seductive idea that if only enough information can be assembled and surfaced, clarity and control will follow.

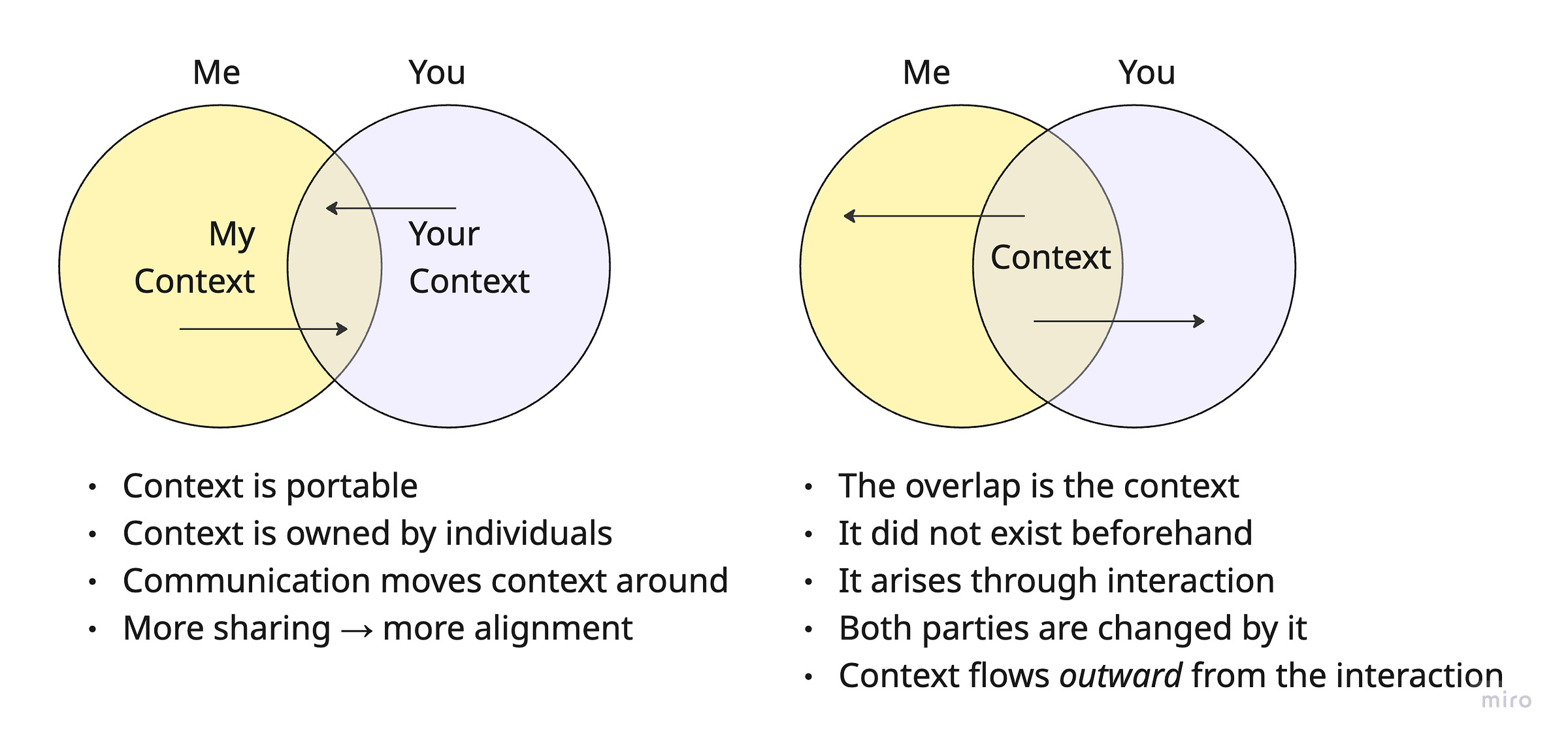

Context engineering frequently treats context as a package that can be handed over or merged. I’ll share—or my prompt or retrieval system will share — what I know; you’ll share what you know (the receiver’s context); and we’ll both have our needs met.

This assumes that shared context can be constructed by combining individual contexts and that understanding is the overlap between what each party already knows. AI is pushing knowledge work toward an extreme single-player mode: after the pandemic normalized remote and asynchronous work, individuals now operate amid oceans of markdown files and “context,” endlessly recombining and remixing information while interacting less and generating little truly shared (or new) context.

Translated to leadership, this is similar to the idea that alignment can be achieved by cascading context downward and aggregating information upward, especially if an LLM can sit atop that context and synthesize it.

But context is produced through the interactions themselves. Context, in this sense, is not something actors bring into the room and pool together. It is something the system produces as they engage with one another. Context is as much a function of framing and interaction as of conditions.

Transmission vs. Enactment

The classic Shannon-Weaver model boils down communication into a transmission problem:

With context serving as background needed to interpret the message correctly. This is akin to asking participants to complete the pre-read before the meeting.

The populist AI version:

If vendor narratives are taken at face value, context becomes a kind of universal solvent: pour in enough of it and magically you get clarity.

But we all know that a pre-read alone does not make a meeting. The interactions make the meeting. The 4E model of cognition (embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive) reminds us that understanding involves active engagement within a shared situation. It happens through bodies, tools, environment, and interaction, rather than the passive reconstruction of information.

The meeting, and the interactions within it, generate context.

Context engineering is, in many settings, interaction design.

Leader As Interaction Designer

Shifting to leadership…

The broadcast model treats leadership communication as a transmission problem: deliver enough context so others can reconstruct the intended decision. Conversely, commander’s intent (and 4E cognition) reflects a different theory of understanding. It assumes alignment emerges through interaction with the situation, not from decoding a message.

Leaders, therefore, do not simply broadcast intent; they refine it with their teams through dialogue, backbriefs, scenario exploration, and continuous adjustment, so that intent becomes the context within which decisions are made, not just an explanation of what should happen.

There is nothing new or novel about this idea. It is supported across fields including enactivist cognitive science, distributed cognition, sensemaking theory, and complexity science, all of which treat understanding as something that emerges from interaction rather than something transmitted as information. It is worth reiterating, however, amidst the current AI context firehose.

And Context Matters…

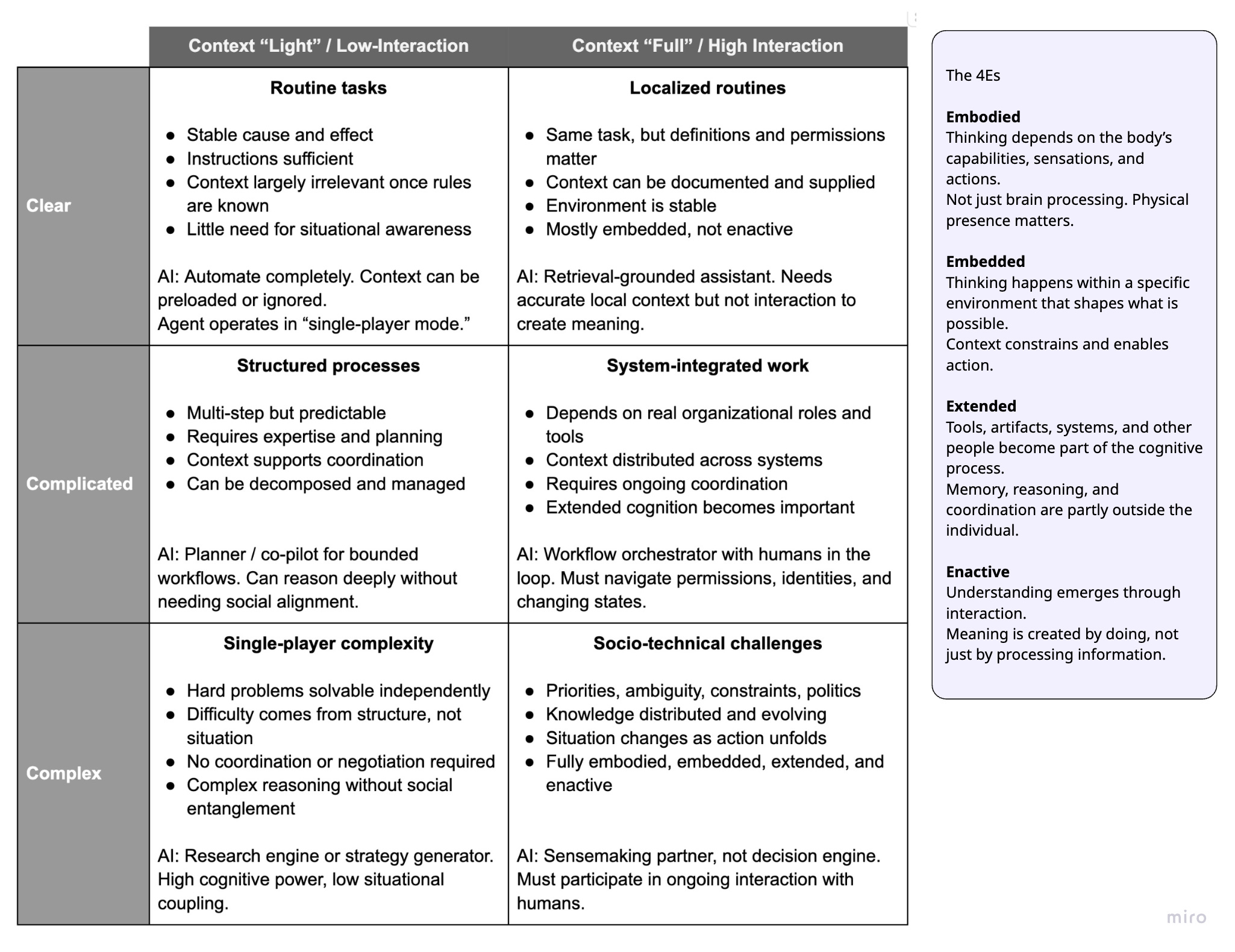

I’ll close with a table I have been working on and adapting. The key point here is that you can apply these ideas just as easily to leadership as to “context engineering”. And if context engineering, especially in context-rich, high-interaction settings, is more akin to interaction design, then… guess what: leaders are interaction designers 🙂.

It also helps to acknowledge that not all decisions require the same kind of context. In some cases, little situational awareness is needed once rules are clear; in others, context can be documented, retrieved, and supplied ahead of time; and in still others, context cannot be separated from the activity itself because it emerges through coordination and action as events unfold.

It’s like we are recognising the need to learn anthropologic communication all over again with AI while pretending that we do not need to.

I see you there, sneaking in the framework that starts with C!

The ontological battle you outline seems to be one we’re destined to keep cycling - perhaps because there are situations where the messaging model can work and when it does, it seems so efficient.

I’m intrigued. Across all the companies you’re working with, how many use different ways of working for different kinds of work? Vs those who are pushing for a universal process?