TBM 362: How (And Why) We Help

What if, in your attempt to help, you're hurting yourself and maybe even others?

Can the outcome still be wrong if it meets the needs of the majority?

Is trying to buck the system always a form of slow, inevitable self-sabotage?

Do big consulting firms and their playbook-driven transformations drive you up the wall? Or is it the systems thinkers, the complexity "whisperers", and context hand-wavers who get under your skin?

This post is one of my more personal posts, though I don't get there until the end. The inspiration for the post started with a conversation with a frustrated change agent, lamenting over the actions of a big consulting firm at their company. I could see my frustration in their frustration and my self-sabotage in their self-sabotage. It struck a chord. It got me thinking about the product advice "industry" in general, modes of help, and personal sanity and well-being?

It starts by comparing two types of consulting, and using that as a springboard, we start exploring the hard questions.

The Gap

The dominant approach in the consulting industry follows this pattern:

Paint a compelling picture of what "great" looks like. Name it. Point to exemplar companies that already do it.

Diagnose the gap. Start with stakeholder interviews to create a sense of inclusion and surface known pain points. Then, run an assessment to show how far the team, group, or org is from the ideal (usually far, but fixable with the right roadmap).

Share compelling case studies with comparable companies. Convince leadership that transformation is urgent, necessary, and totally doable (with the right partner, of course).

Get key leaders personally invested—make it their transformation, something their success (and bonus) now depends on.

Start with a high-performing team and showcase early wins.

Scale what worked. Roll it out org-wide while encouraging mindset shifts and celebrating change champions.

In short, outside experts (assumedly unbiased and with experience working with/for "the best") diagnose the system, define the ideal, and guide leadership through a rational plan to close the gap.

Supply = Demand.

While it's easy to dismiss the standard consulting approach as formulaic or unlikely to spark deep systemic change, I believe it is also what makes it politically viable, repeatable, and relatively low-risk. It's the selling point. The dominant consulting model "works" because it aligns with how many senior executives think and their political environments. It offers plausible certainty, external validation, and answers to important (and difficult) questions.

And lest we frame this only in terms of big companies, do these taglines look familiar?

"A podcast about mastering the best of what other people have already figured out."

"Each episode, I deconstruct world-class performers from eclectic areas (investing, sports, business, art, etc.) to extract the tactics and tools you can use."

"[We] decode the stories, secrets, and skills of the world's sharpest minds and most fascinating people, and turn their wisdom into practical advice you can use."

"Interviews with world-class product leaders and growth experts to uncover concrete, actionable, and tactical advice to help you build, launch, and grow your own product."

I think it is also fair to say—given the consumption of countless podcasts and books that follow this model—that there's also something innately "human" in our hopes/desires to believe that

The answers are already out there

That success can be reverse-engineered, and that

If we follow the right blueprint, we, too, can achieve greatness.

And that if we play our cards right, we can do so without having to sit too long in the uncertainty, contradiction, and messiness of our current state.

Emergent and Relational

However, this is not the only view of consulting.

For example, Peter Block advocates for a model focused on building the client's capacity for reflection, ownership, and self-directed change rather than imposing external solutions. As he puts it in Flawless Consulting:

What is fundamentally corrupt in the process is the idea that one person knows and the other does not.

And

We have a deep-seated and institutionalized habit of focusing on needs and deficiencies as a means of improvement. As if we or our organizations were broken and needed to be fixed. While this may be helpful at times, we have gone way overboard—to the point where we have become well defended against 'constructive criticism'... A more powerful way is to focus on what is working well and what we are good at.

If a client wants the traditional model, Block doesn't shame them. But he sees it as part of the consultant's responsibility to gently challenge that frame and open up space for a different kind of engagement. It's not a cut-and-dry affair. It's more like what trained psychologists face: someone might come in asking for X, but the real work lies in exploring whether Y might better serve them. The task is to honor the presenting need while creating room for deeper transformation.

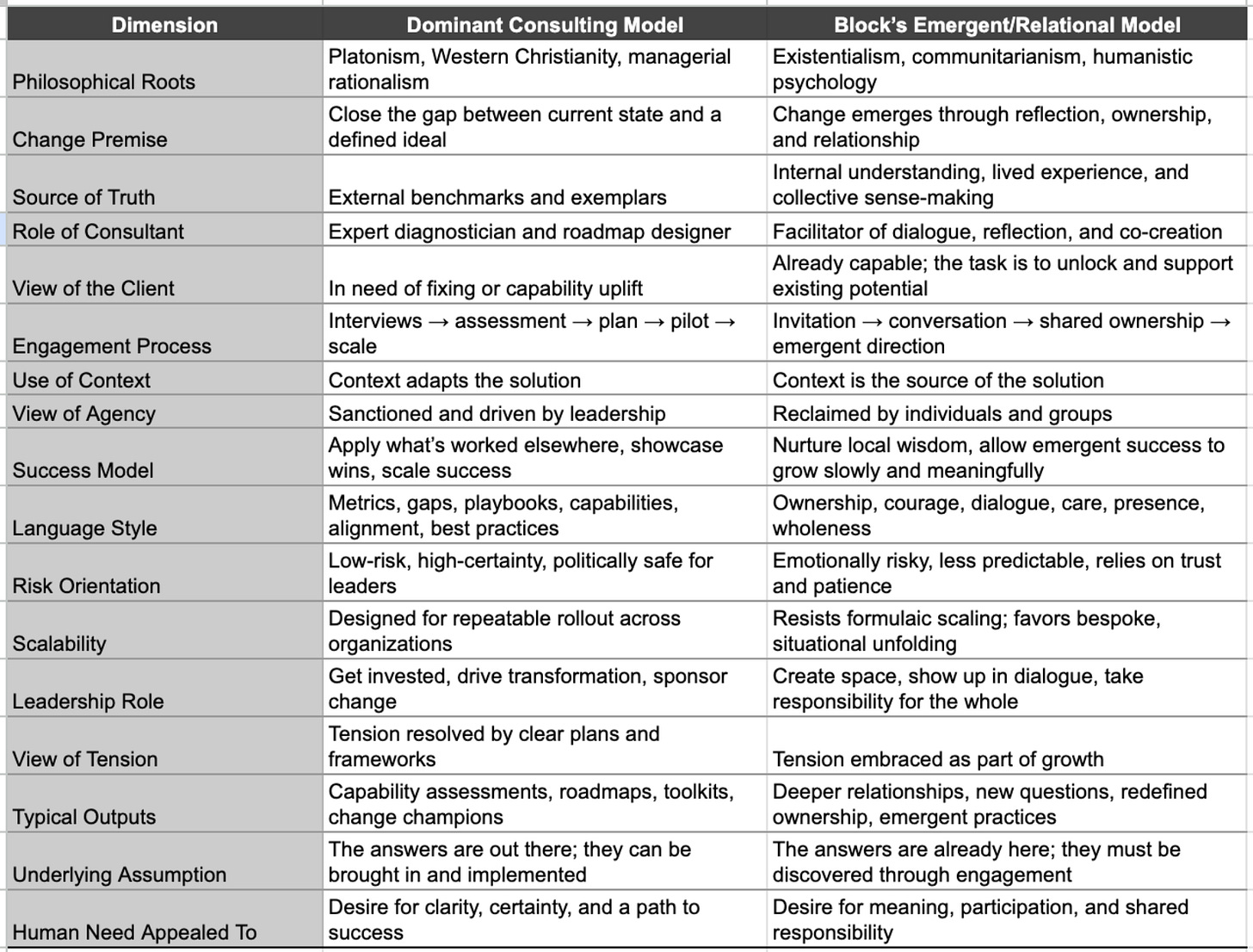

Comparing The Two

If you squint, the dominant consulting model echoes traditions like Platonism or Western Christianity. It involves an ideal state, a gap, and an expert guide to help close that gap. The model is hierarchical, prescriptive, and rooted in external authority.

Block's approach, by contrast, blends existentialism, communitarianism, personal responsibility, and courage…

The price of change is measured by our will and courage, our persistence, in the face of difficulty.

…but always in the context of relationship, dialogue, and shared ownership.

Convening is about creating a place and an invitation for people to show up and take responsibility for the well‑being of the whole.

It's less about applying a blueprint and more about creating the space for people to rediscover their agency together. It's also a fascinating mix of Eastern and Western ideas.

Each of these views also carries a different take on context.

In the dominant consulting model, context is a variable that needs to be understood so the right playbook can be customized and applied effectively. It's something to factor into the solution, but the solution largely remains intact. Truth is assumed to exist outside the situation, and the role of the expert is to adapt that truth to local conditions.

In Block's view, the consultant's role is not to bend the model to fit the context but to help people within the system see that they ARE the context and that change emerges through their engagement with it. It's inherently relational, co-designed, and shaped through dialogue. The consultant doesn't apply a solution to the context—they help the solution grow out of it.

The Big Question

If you work in a system shaped by one model but believe in another, the tension is real. Maybe the organization favors gap thinking and elevates context-free expertise. Maybe you lean toward reflection, dialogue, and emergence. Serving others means meeting them where they are.

But does that mean reinforcing a frame you don't believe in?

Is it more respectful to work within the system or to question it?

What if the only help that's welcome is the kind you wouldn't normally offer?

And what if you've held your view for so long that it's hard to see the other as valid?

What do we owe our clients (or colleagues)? Is it expertise and direction or the time, space, and trust to help them find their own way?

An operations leader described the tension perfectly (extracted from my interview notes):

The leaders here at [Company] are completely obsessed with the product operating model. We did the assessment offered by [Consulting Firm] and scored low in many areas. In the rooms I'm in, there's a lot of talk about whether we have the right people on board. But I feel torn personally.

On one hand, I feel like we're sugarcoating many of the really hard questions. We're ignoring the current reality, and maybe even what has brought us to where we are now. I feel the people here are totally capable of learning those things. But now it seems like we're all marching to the transformation narrative without anyone being part of it. Having outsiders come in suddenly doesn't help with that, either. But I'm stuck on a question. Maybe I should play along with it? Perhaps this is what will work at [Company]? Maybe I'm imposing my beliefs too much on my approach?

What a powerful observation.

The clash of narratives is so stark. The belief in others and their capabilities sits alongside the pressure to follow a script and prove that transformation is underway. The dissonance between a change that is owned and a change that is installed. Between the slow work of building shared understanding and the fast optics of scoring well on someone else's rubric. And the human question: Am I honoring what this group truly needs, or simply reacting to something that makes me uncomfortable?

Moving Atoms

The choice of what hat we wear is ultimately up to us. Despite the environment, we have some agency over how we show up and move the atoms around us.

We can wear the:

Pragmatist's hat, aiming for progress and alignment within the system we're in (utilitarian traditions).

Purist's hat, staying true to our personal convictions even when they clash with the dominant view (Sartre, Camus, Arendt).

Integrator's hat, working skillfully within constraints, shaping change through presence, dialogue, and practical judgment (MacIntyre, Block).

Advocate's hat, using our voice, position, or access to create space for others, especially those whose perspectives have been marginalized or ignored (Freire, Crenshaw)

Expert's hat, offering structure, confidence, and tested answers to help others close the gap between where they are and where they want to go (Plato, Kant, modern consulting traditions)

And more – the bridge-builder (Buber), the healer (bell hooks), the trickster (James C. Scott), the witness (Thomas Merton), the quiet subverter (Foucault), or the caregiver (Noddings, Tronto)—each carrying their own logic for how to move well in the presence of others.

None of these hats resolves the tension, but naming them can help us see it more clearly. And maybe that's the more important move: becoming aware that we carry a view at all and asking whether it's guiding us toward what we care about.

That's the shift: from moving through our work unconsciously to taking responsibility for how we show up in the presence of others. The latter may not be easier, but it is more honest.

Personal Reflection

In my career, I have often found myself caught up in the emotion of the moment. I responded passionately, sometimes defensively. I came to the aid of others. I reacted quickly when I felt diminished or unseen. With time and distance, the connections to childhood experiences became clear. An executive saying, "Why don't you just…" could hit with the same emotional force as a parent's frustrated question. Coming to the defense of a misunderstood coworker could stir the same urgency I once felt defending a parent or myself.

Internally, I wrestled with questions of meaning, responsibility, and what I believed. Externally, it often looked like contradiction or even self-sabotage. Working through this has been a work in progress. My views have shifted over time, shaped by lived experience and the people I've been close to inside complex systems.

The last two years have made the tension even clearer. The workplace is often a collision of beliefs, incentives, and power. People do harm—sometimes without realizing it, and sometimes out in the open. Some truly believe they are helping. Others are protecting status or territory. If you are sensitive to these dynamics, it can put you in a difficult place. There is a constant pull between simplifying the world to make it manageable and staying with the mess long enough to understand it, and yourself, more fully.

I do not have the answers, and I am not a philosopher. But it seems that now more than ever, a little more self-awareness and awareness of others might help.

To readers on the same journey, I'll re-quote the crux:

None of these hats resolves the tension, but naming them can help us see it more clearly. And maybe that's the more important move: becoming aware that we carry a view at all and asking whether it's guiding us toward what we care about.

That's the shift: from moving through our work unconsciously to taking responsibility for how we show up in the presence of others. The latter may not be easier, but it is more honest.

Great reflection. At the risk of falling prey to cognitive bias: I see this as the difference between teaching people methods versus just showing them patterns and then ask them to think for themselves.

Excellent Article, love it!

Is there maybe another Tension when the 2 models drift into each other? Sometimes it might not be clear are your consultants in model 1 or 2. A legacy modernization Team gets external support, how are the externals operating? They are individuals working for different companies. The internal Team gets the mandate to modernize with the outside help. I find the Idea to zoom out and ask how are we working together and in which Dimension are we on which Model an interesting thought.