TBM 326: Adhocracies and Bureaucracies

A quick post this week as I've been busy starting a new full-time job. I'm back in the PM game. Wish me luck! I will keep writing as always, so thank you for supporting my writing habit.

Rapid-growth tech companies often operate as adhocracies—they do whatever it takes to grow, move quickly, etc. The 0-1 stage is characterized by a lot of startup-wide bridging and fluidity. After the 0-1 stage, there's a tendency to favor team independence, clear spheres of ownership, and fewer global/mandated processes and rules.

In comparison, large enterprises can feel like rigid bureaucracies. Getting anything done is incredibly difficult. There are tons of centralized rules and mandated ways of working. When these companies try to "transform," they must descale, de-couple, and disentangle the institutionalized incoherence.

Implicit vs. Explicit Bureaucracy

With rapid-growth companies, I have observed that in the quest for minimal bureaucracy, there is often an accumulation of implicit bureaucracy. Unspoken layers of constraints, norms, and rules accumulate. The culture discourages talking about these things—it is important to keep up the veneer of independence. "People should just be able to work it out! This is why we try to hire the best! We shouldn't need new processes to fix this!"

In many cases, the mess gets offloaded onto integrative roles like program managers, centralized ops, researchers, platform teams, etc. That way, teams can preserve the facade of independence while the integrators soak up the complexity. Ironically, it can often be harder to do these types of roles in a rapid-growth tech company vs. a large enterprise due to the inertia around decentralization.

The Cycle

As it gets harder and harder to get things done, leaders sense the creeping (but largely implicit) bureaucracy and get paranoid. "What's going on?" People's reluctance to address it openly exacerbates the problem ("We were told to bring solutions, not problems!"). This kicks off a wicked cycle where leaders try to quash the rising tide of bureaucracy by playing process whack-a-mole and singling out individuals instead of digging deeper. Until the house of cards collapses, at which point you must do something drastic like layoffs, org-flattening, and/or a hard swing over to top-down control.

The Valley

I was recently chatting about these swings with someone from a famous, often-discussed rapid-growth tech company, and I shared Dr. Ron Westrum's Organizational Typologies as a point of reference.

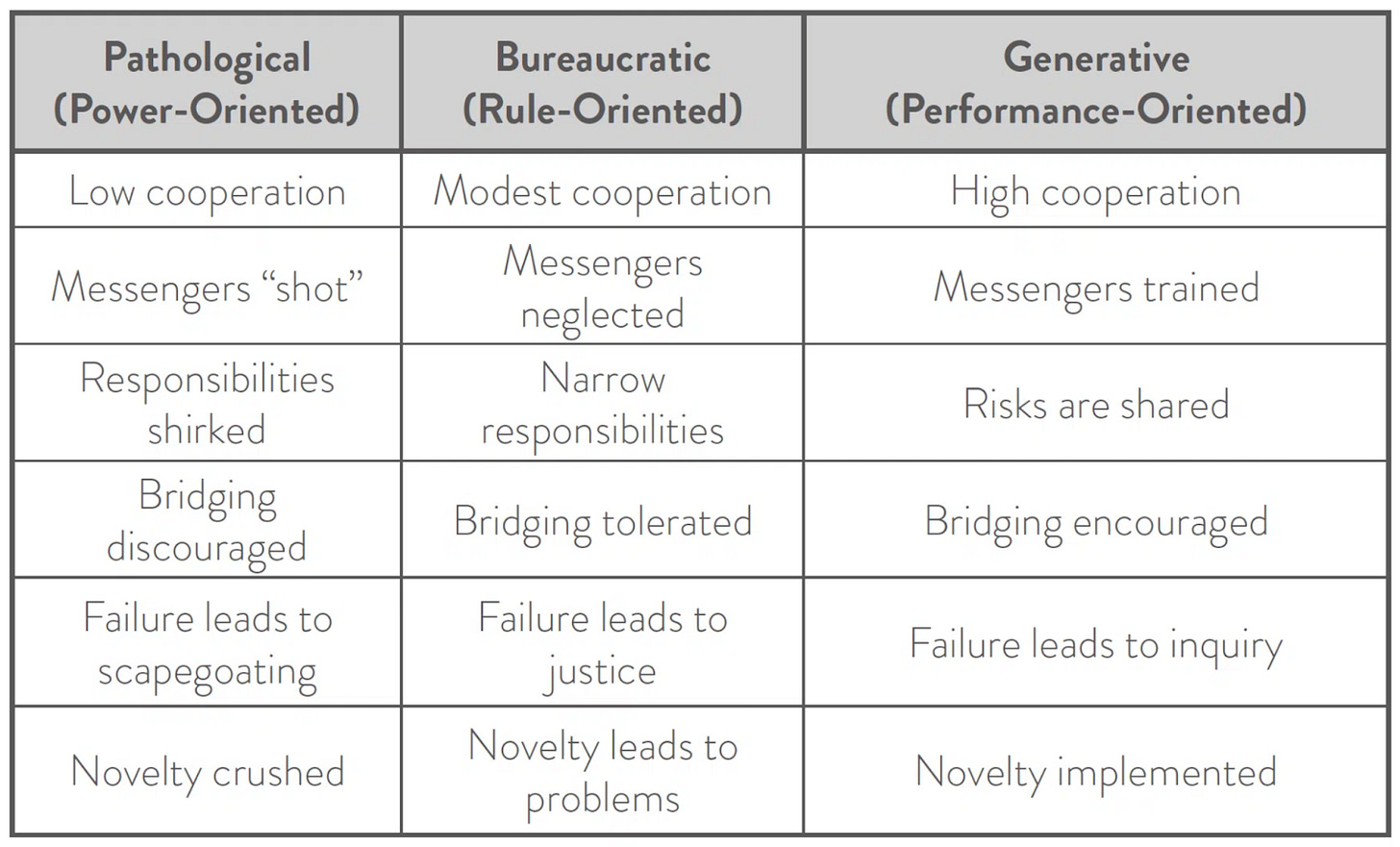

I know there are several issues with the model from sharing it in the past, but it served the conversation well. Westrum divides organizations into three categories—pathological, bureaucratic, and generative—with the important clarification that a company could have many different typologies operating at once.

The conversation was fascinating—this quote in particular:

Here, ownership as a concept is diametrically opposed to a more collectivist, helping mindset. People are really motivated to own things – which means they're not too interested in helping with stuff that someone else 'owns'. 'Ownership' = 'getting credit' in this environment.

Within a given organization the cultures can vary wildly. My team used to report into global [department name] which was far to the generative end (though soon to end unfortunately with a major import of leaders from [company known to be less generative]). Whereas the teams that are 'closer to the sun' e.g., [CEO and founder] are much more pathological. There's a complete skip of the bureaucratic column here.

The more integrative "global" (glue, integrative) group cultures tend to be more generative, but bridging was challenging due to team independence (local generativity, I'm guessing) and disincentives around cooperation, which the leadership team mirrored and modeled!

And, to top it off, there was an influx of more power-oriented leaders.

Anything to avoid explicit rules and processes.

(If you've noticed the language around layoffs recently, some ideas here may fully click.)

Unless you've worked in Silicon Valley, it can be hard to fully understand the heady mix of process-phobia, individualism, generative approaches (performance-oriented), and pathological currents. People often point to the valley as being "agile," and this is likely correct given a team-centric interpretation of the term, but when it comes to types of agility that are more collectivist and involve collaboration across groups, the picture is much more complex.

In rapid-growth companies, teams knowingly avoid and work around the global teams, and the pressure is on the global teams to interject and bridge. In big enterprises, the opposite is true: local teams are at the whim and whimsy of the global rules.

Thoughts…

Why is this important? A couple reasons:

Silicon Valley will always argue that all you need to do is hire the best, hire great leaders, have an audacious mission, and get out of the way. Process is evil! Process is for mediocre people! Avoid bureaucracy at all costs!

While a key driver for its success, these biases can create blind spots around the potential of bridging/global functions and more collectivist continuous improvement efforts spanning groups.

Often, in the quest to stamp out bureaucracy, leaders create even MORE bureaucracy, which is implicit and difficult to navigate or understand. Or there's a shift to a power orientation. Or there's a collapse. Or all of the above.

One person's bureaucracy and heavyweight process is another person's "Let's create some lightweight working agreements so we can tackle this bigger problem together." It is worth discussing this with your team.

Large enterprises that are "transforming" should take inspiration from everywhere but remember that the fundamental motion they are undertaking is not the Silicon Valley challenge. It is more of a get the train moving (separate the train cars to descale) vs. an attempt to fix the train while it is barreling down the tracks (scaling and taming pendulum swings). This is especially relevant if you attempt a "projects to products" or product operating model shift. There is a high likelihood that the next couple of years will look very different from "the movies," and that is OK.

Consider the value of scaffolding and temporary process. Ambitious things often require some structure. If you institutionalize that structure, you run the risk of hiding behind it. I think is applicable for both companies that are scaling up, and companies looking to de-scale and de-couple.

Thanks again for supporting the newsletter across different career adventures.

And then if the company makes enough money when they get large they'll hire huge bureaucracies doing a lot of inefficient project/program management having synch meetings about spreadsheet update meetings so that execs that came up in the adhocracy can pretend they still work in an adhocracy and call it a "bottoms up culture"

Hi John, many thanks for your write ups, I follow them closely. This article prompted me to an op-ed to rethink bureaucracies, if you don't mind. The word "bureaucracy" creates unpleasant associations with slowness and inflexibility. Yet I'd invite everyone to consider a more neutral and utilitarian view on it.

Corporations have to follow a rhythm of sharing quarterly updates to shareholders. This is particularly true for publicly traded corporations, where the quarterly update cycle gave growth to a sub-industry of market analysis and prediction. Research analysts make estimations of relevant KPI such as EPS, which are aggregated by financial information providers into a consensus estimate. Company's ability to match up to these estimates, as well as ability to provide reliable forecasts make significant impact on stock price.

In other words, the volatile and unpredictable market values predictability of its participants. This was explicated in multitude of sources, e.g. the seminal work "Organizations in Action" by James Thompson (1967). The author discusses the concept of isolating an organization's core technology from environmental uncertainty. Thompson proposes that organizations employ mechanisms to protect their technical cores from environmental fluctuations, such as buffering, leveling, forecasting, and rationing.

This protection may be achieved through several mechanisms, and one of the most prominent ones is codification of business processes. As time goes by and workforce grows or rotates, it becomes important that new employees continue following processes that have been proved successful - hence processes rule and "explicit bureaucracy" emerges. It also becomes important that employees share internal rules of engagement to reduce internal cost of micro-transactions, therefore a set of unspoken rituals emerges, which is referred in the article as "implicit bureaucracy".

Bureaucracy permeates corporate world. Procurement departments of large corporations or government require that prospective suppliers prove they are sufficiently bureaucratic. An entire industry of corporate certifications offers to certify advanced level of bureaucracy in a corporation through ISO 27001, ISAE 3402 aka SOC 1, and endless assortment of other certifications. Vendors without proof of bureaucracy don't have a good chance, though.

Codified Processes bring in significant operational advantages:

* In terms of Cynefin, this is a major tool for transitioning from Complicated domain into Simple/Obvious domain and enabling the Sense-Categorize-Respond action logic.

* The above unlocks scaling of business processes by making them clearer to wider groups of potential workforce candidates. Companies with tens of thousands of employees cannot rely on scaling by hiring only "the best of the best", but rather have to efficiently utilize whatever candidates can be attracted from the labor market.

* Repeatable processes remove dependency on individual team members and contribute to longevity and predictability of execution.

* Codified processes are often seen as an enabler of transparency, which is considered a desirable component of an organizational culture. Transparency is achieved by shared understanding of which knowledge artifacts need to be produced and published during decision making.

* Codified processes are also often regarded as a pre-requisite to pursuing equality or equity in a work place, so that everybody is subject to the same process, although this alone isn't any guarantee of fairness, equality or equity.

Given the above list of advantages there should be no surprise about proliferation of "bureaucracy" in business relationships.

Silicon Valley is no exception here, and deals with bureaucracy in three expected ways:

* Avoid: startups aren't yet expected to repeatably participate in corporate/government procurement process; they rather rely on personal networks of founders, VCs and early employees to secure launch clients. Similarly, due diligence process of VCs focuses on personalities in a startup team, rather than on their ability to handle changes of team members. Personality-based ecosystem allows to compromise predictable long-term execution in favor of short-term business agility. This dynamics radically changes during a liquidity event, when the startup does IPO or gets bought by a larger company with an elaborate bureaucratic tradition.

* Adopt: VC funds themselves operate in accordance to well-known and codified process of funding rounds. Departure from this process would confuse LPs and founders, so this is a domain of pretty bureaucratic relationships.

* Embrace: startups with business models that require scaling out through engaging wide number of people (e.g. crowd testing, food delivery or ride hailing) become perfect bureaucratic machines. They build algorithmic dictators, which fully determine nature and conditions of transactions (e.g. ride fee) so that human clients don't even have counterparts to negotiate with.

I'd argue that Westrum's model quoted in the article could be a little bit updated along the following lines. Bureaucracy vs. adhocracy axis could be made a separate dimension from Power-oriented vs. Performance-oriented axis. Working relations may assume different positions along these two axes, and it would be curios to see if any particular combination correlates with short- and long-term business success.

In conclusion, "bureaucracy" in sense of acceptance of codified processes over individual voluntarism of "adhocracy" introduces significant operational advantages. Any serious talks about stamping it out in large companies seem futile at best. A more pragmatic approach would be to consider it as a effective alignment tool. As any tools, it needs to be employed properly, maintained and sharpened.

I could think of a metaphor of an "evergreen bureaucracy", in which master gardeners (aka VP of Bureaucracy) monitor existing processes for their efficiency, solicit continuous feedback from the shop floor, and then trim, update and retire processes as needed. Messengers should be welcomed or better yet, trained, as suggested in the Westrum model. This approach would require serious OCM and cultivation of organization willingness to continuous change - yet doing it by moving from process to process while staying in the bureaucratic realm.