TBM 314: Using Enabling Constraints for Situational Awareness

Some quick notes:

I’m doing a free 1hr workshop on the North Star Framework (Oct 9th | 9AM PDT)

I am offering a Western and Central Europe-timezone-friendly run of my prioritization workshop on October 24th. It also works for the East Coast in the US. I will be ready to go at 6AM PDT!

Warning: If you are looking for something simple and actionable, this post might be too abstract. I talk about sewage. But I do get to something at the end.

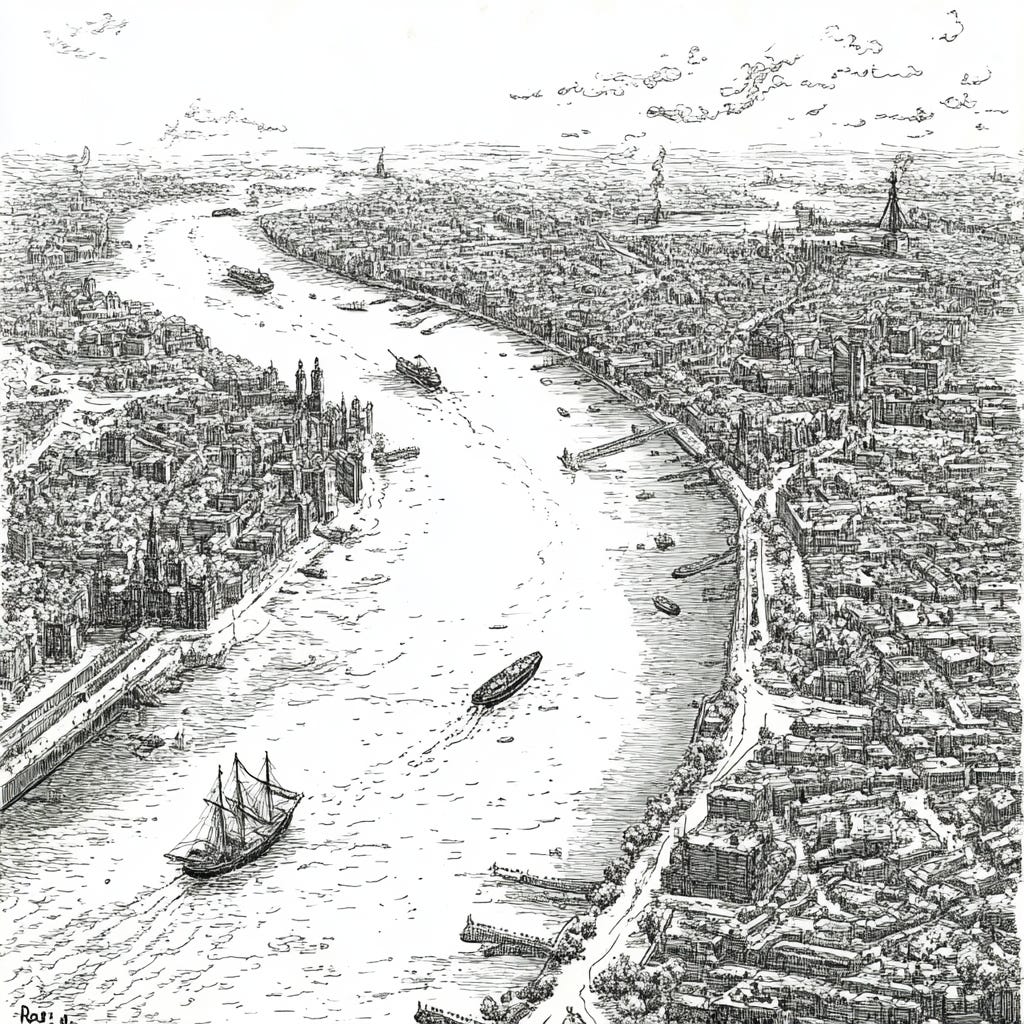

The Great Stink

It is almost impossible to scale quickly without introducing some incoherence and inefficiency. To understand this, one need only read the history of boom towns, gold-rush towns, and newly thriving ports and cities.

Take London.

During the Industrial Revolution, the rapid influx of people caused overcrowding, led to sprawl and haphazard city planning, and strained the aging sewage infrastructure. "A dirtier or more wretched place he had never seen," writes Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist.

Things were getting stinky.

The situation had to get worse before it got better. It took a cholera outbreak AND the "Great Stink" (when the accumulated human waste in the Thames smelled so bad that it disrupted parliamentary proceedings) to force the government to act and construct a better sewage system.

The action did not come easily:

Lord John Manners, the First Commissioner of Works, deflected blame. He claimed that the Thames was not under his jurisdiction. In 1858, Lord Palmerston's government fell, and Lord Derby's administration took over, which threw a wrench into any kind of consolidated response. It was too easy to pass the buck and too difficult to take responsibility.

The prevailing theory at the time was that diseases were transmitted through bad-smelling air instead of contaminated water. To kill the stench, officials poured vast quantities of lime and carbolic acid into the Thames to mask the smell (it reminds me of what smokers do with air fresheners). It took three successive cholera outbreaks between 1831 and 1843, killing 31,411, for people to deeply question that theory and accept new research.

Steve Bruce writes:

What led to the Great Stink of 1858 was, ironically, every step taken by the citizens of London in their efforts to distance themselves from their own waste products, and the almost absolute neglect of Government and its commissions that were responsible for their care.

Bruce quotes scientist Michael Faraday waving the warning flag:

The condition in which I saw the Thames may perhaps be considered as exceptional, but it ought to be an impossible state; instead of which, I fear it is rapidly becoming the general condition. If we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.

But action required something visceral and structural. Structurally, there had been no centralized authority over the sewage systems. The Metropolitan Commission of Sewers (1848) and Metropolitan Board of Works (1855), along with the appointment of Joseph Bazalgette, provided the necessary structure. The stench disrupting parliament took care of the "something visceral." The people in power couldn't ignore the problem if they wanted to show up at parliament.

Scale and Enabling Constraints

I was thinking about the Great Stink recently, reflecting on the last decade (or more) in tech. Assuming for a moment that some incoherence and inefficiency will always accompany rapid growth and scale, one has to ask: "Is there anything you can do about it? Or is passing the wicked problem threshold an inevitable byproduct of scale and growth, with the only answer being a violent, oversimplified reset of sorts once things have gotten really bad?"

Does it have to waft into parliament?

I am a (perhaps naive) optimist. While we can't prevent this dynamic completely, I think you can do things as a team to smooth out the normal business pendulum swings between growth and efficiency, exploration and "extraction," top line and bottom line, and capital efficiency and near-term profitability. There's always a lag, but better sense-making and observability can close the loop a bit.

An area I've been thinking a lot about is the role of enabling constraints in making sense of potentially incoherent situations during periods of rapid growth, uncertainty, etc. Granted, this might be better advice for the "next time around," but better now than never.

Let's start with what we tend to observe during periods of rapid growth:

Hiring rapidly, including throwing people at problems instead of more graceful fixes

Spinning up new initiatives quickly, with minimal oversight

An exponential increase in dependencies, process overhead, etc.

Focusing on either near-term revenue or lofty, far-off "innovation."

Feedback loops degrade, factions form. Breakdown in systems, tools, etc.

Rapid information/context loss (people leaving and the % of people who lack core context).

Now, consider how you might artfully use enabling constraints to get some early warning that these things are happening before it is too late. Yes, you can rely on people calling it out, but how reliable is that once the incoherence grows?

Some examples of potentially graceful enabling constraints:

Some set of gates to prevent teams from hiring people to patch problems. You must battle the perverse incentives for large teams.

Any guardrails around the customer experience, outages, onboarding times, etc. Trip the guardrail—pay attention. For teams to show up at product review, they need to have nominated ~5 core health metrics (along with thresholds) that they revisit regularly.

Anything that can help limit work in progress. One option might be a combination of a WIP limit and a "finish before you start" policy for large, high-dependency projects. You might also limit when certain types of efforts can start quarterly to have fewer "whoops, we somehow agreed on that mid-quarter without anyone weighing in" effects.

Whenever you have an initiative involving more than N people and >N teams, you must run it through a more rigorous, multi-perspective vetting process. When a team is pulled between more than N efforts, it triggers an immediate "tie resolution" meeting, whereby they get outside support to help them decide on a single effort to focus on.

Do a mandatory, well-facilitated retro on things involving a certain amount of $ and capacity. Invite execs.

The theme here is "rules" that are easy to follow and serve as early warning mechanisms. They make you think, make you pay attention, and act as a catalyst for discussions. Instead of process gates that people routinely ignore or work around, these are solid constraints. Of course, the process-phobes among you might cringe at these ideas—why don't we just let people work these things out?—but I guarantee you that there is still plenty to be discussed and worked out.

To close…

What enabling constraints could you use at your company to catch incoherence before it gets too bad?

Imagine the reverse question now that we are navigating a period of efficiency. What are the risks here? What constraints might be useful?

I am also an optimist. But somehow I also tend to have mini-breakdowns, when it seems as if „the parliament“ does not smell the stink of accumulated technical debt, in a hugely successful product line (we just launched an new, very successful product, working bravely around all the good and bad of the exiting product line).

While everyone intellectually understands the need to modernize the existing tech stack, and in fact we are scaling up fast, we are fragmented into different parties.

One group, the managers, make sure to add „headcount“, following KPIs like „by the end of the year 80% of development works on the future!“ Another group, product marketing, does not have the luxury to focus only on the future product line. For them the future is now. My group, the techies, thinks the future is mostly in technology, so we are ramping up infrastructure at an amazing speed, often in dis-connected silos. Without well defined product increments, we can decide on our own how much and where to integrate.

Still, as an optimist, having witnessed similar situations in the past, I know that when the „stink“ will be apparent to everyone, we will pull together.

As you say: it is about awareness and presence. About seeing what the others see. About feeling accountable for the things we can influence and acting on them. Even if the action itself might be heavily criticized by others.

Prevent layered prioritization/allocation approaches, e.g., having priority 1 and 2 projects, an even more important priority with fixed delivery dates, all combined with a detailed allocation of team resources to different kinds of project or non-project work.