I am working on Part 2 of last week's post. Given the topic's weight, it will take some time. I appreciate all the feedback.

This week, someone shared a story that struck a chord. It helped me put a personal challenge into perspective. The basic point was this:

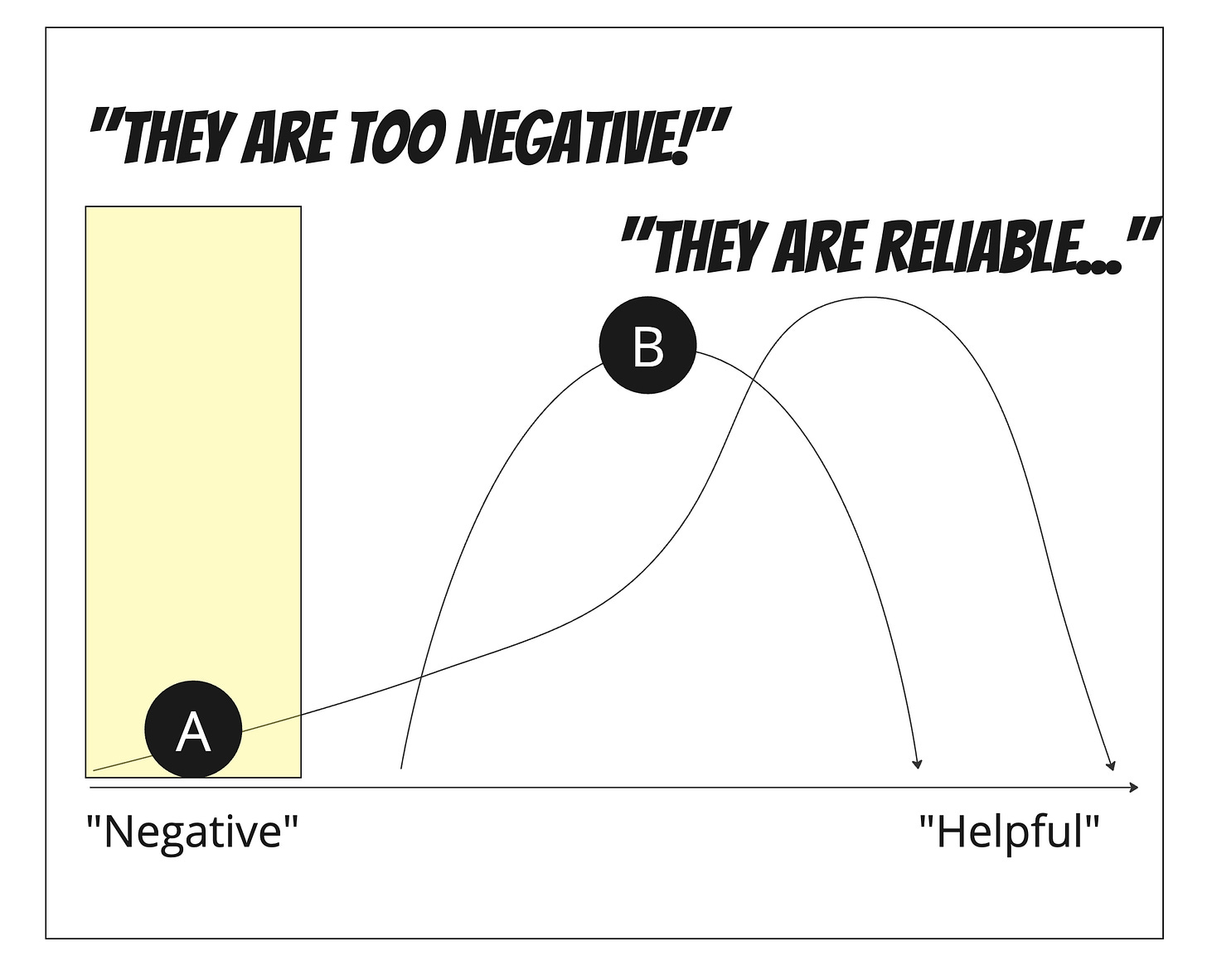

When you are passionate about helping others, improving ways of working, challenging the status quo on behalf of those hurt by the status quo, etc., you will invariably have an "off day." The sad reality is that somebody will judge you harshly for your off days. People will seize that moment to paint you as too theoretical, caustic, troublesome, polarizing, or too [whatever]. And this adds up over time, even if you're at your best 90% of the time.

Why?

Research has shown that negative events are more salient and that we process them more thoroughly (negativity bias)

A misstep is an opportunity to reinforce in-group and out-group stereotypes (social identity theory)

When we have a bad day, we attribute it to our environment. When someone else has a bad day, we attribute it to their character (fundamental attribution error)

Halos and Horns. A single event can give some a halo or give them horns.

People threatened by a shift in the status quo, or who generally disagree with you, will use your "off day" as justification (confirmation bias)

Seasoned executives know all this, of course. I had coffee this morning with two "super exec" friends who, over the years, have shown an uncanny ability to avoid this trap. One of them had an interesting point. Paraphrasing:

Remember, for us, staying in a guarded, don't-show-your-cards mode is a learned habit. We couldn't survive otherwise. It is always on. Once you get to VP or above, you learn that even the slightest gasp or eye-roll could be used against you. On some level, people who adopt more informal, org-hierarchy spanning roles have it harder.

They might have been humoring me, and I'm biased, but this point hit home.

I was reflecting recently on how enablement roles often facilitate activities with diverse formal roles and interests. You are in a high-profile position but not a high-formal authority position. One moment, you're talking to the CEO. The next moment, you are talking to a front-line IC. People tell you things they would never tell their managers or put in an engagement survey. As I mentioned in The Integrators Burden:

If so, there is a good chance you have a view of your organization that no one has (not even the CEO). You see and hear things most people don't see. You are taking on an emotional burden that most people don't take on.

Anyway, it is hard.

Unforced Errors

In Clear Thinking, Shane Parish talks about "unforced errors."

All the time and energy you spend fixing your unforced errors comes at the expense of moving toward the outcomes you want. There is a huge advantage in having more of your energy instead go toward achieving your goals instead of fixing your problems.

As much as we would like to exist in work settings that were more generous with "errors" (if "to err is to be human"), the reality is that most situations are not as we wish. We may be able to cultivate such an environment on the small—among a small group of people—but doing so across an organization with competing interests is not feasible.

There are many situations as a change agent where the "upside" of a certain interaction is minimal. Still, the potential downsides—the chance of errors—are high (especially when compounded across many interactions). A great example here is speaking to senior executives. There are chances that you will magically make a good impression and move a problem forward, but they are low. It happens, but it is very, very rare. The chances that you will slip into a hornet's nest are high. The chances that your interaction will be "interesting" and you'll get the treatment most people get when bringing perspectives is higher than both, but it doesn't advance your mission. Plus, since they are likely good at obscuring their true feelings about the exchange, you probably will not know.

In other words, it is a bad bet. Don't do it! Steer away from the conversation! Or have the conversation they expect and use that as a trojan horse to try to pry away the veneer and understand them better. Listen 95% of the time.

If we know we're human, we know humans can't always have a good day, and we know the impact of having a bad day is BAD…then we should avoid unforced errors.

The same lesson applies to letting a situation get worse, even if you hope to improve things over the long term. I received a lot of flack for posting this on LinkedIn. My intent wasn't to advocate for "giving up" but rather to " lose the battle to win the war," so to speak.

Sometimes, the best strategy is to let things implode and burn to the ground. Do nothing. Save your energy. This can be incredibly difficult if you care about people. Not speaking up feels like you are part of the problem. If you're predisposed to care about justice, fairness, representation, sustainability, etc. "doing nothing" feels like an assault on your identity.

"Surely we can do something! Surely people will pause for a moment and listen?! Someone has to say something—it's obvious—what if we could just talk it out? Surely, there's a magical way I could deliver this news, be the change, influence others, and make it happen."

But here's the thing:

The canary dies. The canary does not live to see another day.

There's no honor in shouting into the void. While flattering, "that's interesting" or "that's something to consider" ultimately doesn't do the work.

Timing is everything. Good intentions mean nothing.

You only have a narrow window to influence change at a global level in any organization, and sadly, that window is often after the bad things that you've warned about (and other people have warned about) have happened.

Of course, context is everything, but in many cases, the best strategy is to be there with the best relationships, trust, and confidence after the crash.

Both for whatever change you seek AND for your well-being and energy conservation.

Reflection Questions

And with that, some straightforward questions to ask yourself.

"Given how things are, not how I wish they would be, how are my current actions supporting my long-term mission here?"

"Am I managing my energy for the long term?"

"Given that it is impossible always to have a good day—especially when navigating the thorny mess of change—how can I make the smartest decisions regarding how I apply my energy?"

I know this may seem highly un-John-like, but do think there’s a path here where we show grace to ourselves, and seek long-term positive things without burning out.

The plight of the change agent who is often a consultant (ahem, yes, very familiar with this hat):

"...enablement roles often facilitate activities with diverse formal roles and interests. You are in a high-profile position but not a high-formal authority position."

About a year ago, while I was a FTE, a VP told me to be the change. Yes, I'm unemployed now because #layoffs.

Oh heck yes. I've just witnessed this with a colleague and also experienced it directly (I'm in a non-top-tier consultancy that runs more like a staffing agency) . A VP who I admire for speaking their mind spoke their mind, and...got reassigned from their client because the client VVIP thought the VP's thoughts were 'interesting.' And, I have just been reassigned after trying to introduce change because the turnaround scenario that I was asked to helicopter into needed a 'go to green' plan. I spent 3 weeks assessing and then the first week's worth of 'experiments' as I positioned them, landed well with my team but not with my client. So, onto the exit strategy...