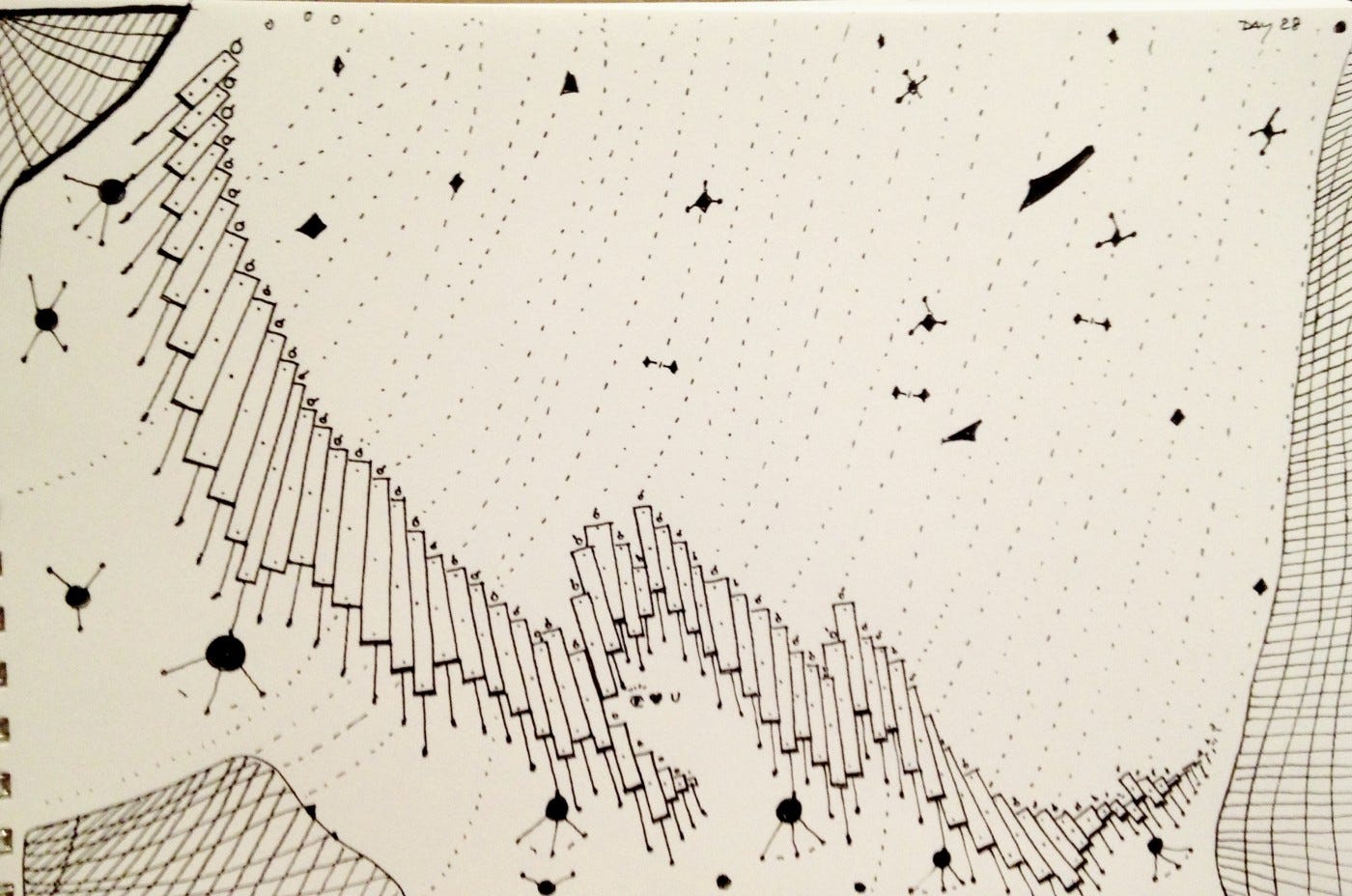

TBM 28/52: First Focus. Then Simplify

A complex problem cannot be simplified.

If you can simplify it, then it isn’t a complex problem.

You may choose to focus energy on a key leverage point, or establish one or more enabling constraints. To make progress, you may choose to selectively ignore things, blur your vision, or think in broad strokes. These approaches will reduce cognitive load and will feel simpler. But they don’t leave us with a simple problem.

Imagine two people:

Person A acknowledges the complex problem, and focuses

Person B doesn’t see the complex problem, and simplifies

Who is more likely to make progress? My money is on A.

A and B’s approaches may seem very similar—at least at first glance. Focus looks like simplification. Simplification looks like focus. But when things go wrong, and unexpected things happen—as they tend to do—Person B will make bad decisions. They’ll pick bad strategies and tactics. When they communicate their assessment to other team members, they’ll spread the lack of context awareness.

If we approach a complex problem like a simple problem we run into trouble (Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework can be a helpful guide here).

In Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt says that a good strategy has a diagnosis (followed by a guiding policy and a set of coherent actions to carry out the guiding policy). A diagnosis…

“...defines or explains the nature of the challenge. A good diagnosis simplifies the often overwhelming complexity of reality by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.

“Simplifies”, in this context, feels more like identifying and prioritizing key levers—not simplifying reality. The “overwhelming complexity of reality” doesn’t magically go away, even if you identify certain aspects as critical. We can choose to ignore reality to make progress, but it is there.

Why is this important?

Teams confuse focus and simplification all the time.

A “simple and memorable” strategy is not necessarily a focused strategy. Simple messaging is not necessarily focused messaging. Simple personas don’t necessarily inspire focused problem solving. In fact, simplification is often a precursor for lack of focus.

Personas are a great example here. Say we have lots of personas/clusters of customers with similar traits. Someone decides that “twelve is too many!”. Based on my experience, teams take one of two approaches:

We PICK 3 of the 12 personas to focus on

We try to create 3 personas that capture the 12 original personas

#1 is focused and focus is hard. #2 is simple. No one will complain about #2, unless they are really paying attention. But is it the best approach?

Once we focus, we can simplify.

We pick three personas to focus on (leaving nine we’ve explicitly decided NOT to focus on). Now we are in a position to simplify. Anyone who has composed a song, or designed an interface, knows how hard it is to make something simple. It is way easier to add lots of musical notes and lots of interface menus. After we focus, we can do the hard work of finding a graceful solution.

Try to bring problems AND solutions. But be prepared to pivot.

It is helpful to align on the nature of a problem before offering solutions. Ideally, we’d sit down with our team, managers, and leaders and explore the problem space together. And then we’d prioritize experiments to try.

But I’ve learned over the years that this is not always possible. In many organizations, people don’t really want the details. “We knew this was hard!” “This is why we hired smart people!” “We does rehashing this do for us?” They want to know what you are going to do to fix the problem. This presents a dilemma. If the problem is complex—and you know it is complex—you’ll be cautious when it comes to suggesting there’s a quick fix (aka simple solution). At a certain point, however, you just have to go for it.

Walk into the meeting (or join the Zoom), present your diagnosis, and advocate for some focused experiments to get things moving.

This is great, as always, John.

What this leaves unsaid, though, is how to avoid inadvertently simplifying, by simply forgetting about what you're not focusing on.

In fact, I'd say it's the way you relate to / preserve what you choose to ignore that determines whether you're adapting a complex posture.

What strategies have you seen people adopt on your travels in order to preserve

- rejected hypotheses

- de-prioritised objectives

- non-core personas

?

This is just word play with the meaning of simplify