(I’m doing a new 3hr workshop on prioritization if anyone is interested)

Someone asked me recently for an example of where I had shifted my perspective.

I blurted out Continuous Improvement without really thinking.

This post explores that shift—or more like crisis.

I have a deep emotional connection to continuous improvement (Kaizen). My view was heavily influenced by my explorations of Lean and Agile starting in 2005. The idea of Kaizen—everyone in the organization—executive to frontline team member—working together to make incremental improvements was extremely appealing to me. I also felt a strong connection to Respect for People, another core pillar of the Toyota Way, which stressed respect, trust, partnership, blameless retrospectives, and teams and individuals evolving their practices.

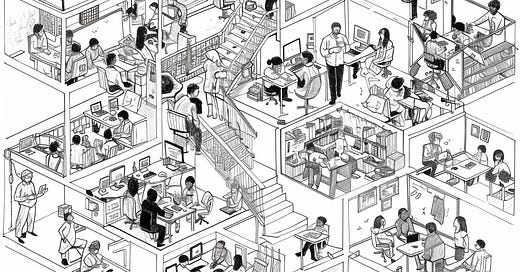

I have always loved this diagram by Bas Vodde and Craig Larmen from their Lean Primer (Version 1.6). I love how it communicates principles, practices, goals, and beliefs. Respect for People and Continuous Improvement are the "pillars".

Especially impactful were Kent Beck's Extreme Programming Explained, Mary and Tom Poppendieck's series of books on Lean, and Joshua Kerievsky's work on Modern Agile, which simultaneously sought to bring Agile back to its roots while "retiring" outdated practices (e.g., Story Points, "scaled agile", rigid role definitions, etc.). I had a great chat with Josh in 2018 when I began my stint at Amplitude.

Josh has a great new book out by the way.

In 2024, I must admit I am having a bit of a personal crisis regarding continuous improvement. It doesn't matter whether we're talking about "high performing" companies and teams, or companies seeking to transform how they work—there is very little talk of continuous improvement.

The language around layoffs in tech is rife with talk of operational efficiency gains, achieving profitability targets, rightsizing, and high-interest rates. There is very little sense that employees were allowed to be part of the solution or path forward (e.g., by recommending areas of cost savings, quality circles, taking pay cuts, etc., similar to Harley-Davidson in the early 1980s, Southwest Airlines in 2001 or 2008, or countless companies mid-pandemic).

Two representative quotes from recent conversations with friends:

We're on a third round of layoffs, and there's a mix of people checking out and freaking out. People have retreated into their silos and are in full wait-and-see mode. It is especially hard for people raising the flag during the quarters and years leading up to all this. We were just steamrolling along. No one listened. No one had time to fix things.

The joke is that [well-known tech company] is about as waterfall as it gets. That’s the least of our worries, though. People hate retrospectives, and it is hard to change anything. We are told to stay in our lane, 'that's just the way it is.' We're good at product, though.

Meanwhile, among companies less impacted by the ups and downs (real or imagined) in tech and deep in their respective transformations, we see the same old copy-paste approaches, outdated practices, and "changing but not really changing." On some fundamental level, when it comes to continuous improvement, there is no real difference between the two: in both cases, you have change imposed on teams and a lack of engagement to co-design the way forward. In both cases, existing power structures remain entrenched.

Here are three more generous interpretations:

Lean/Agile (the mindset, the principles, the "We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it") was deeply subversive, too far ahead of its time, or both.

Inertia reigns supreme in everything but the smallest startups. Change is hard. Sometimes, you are on the winning side of that, and the inertia helps until it stops helping. And sometimes, you are on the losing side of that. You're stuck, and the inertia keeps you stuck. The leadership skills to transform anything are unique.

Companies that practice continuous improvement are extremely rare, and that's OK. It IS just the way it is. Toyota and a handful of other companies were the exceptions, and there was a strong cultural component explaining why they existed.

I have hope, though.

It comes from companies you might not expect. I’m noticing pockets of empowered (and talented) leaders helping real companies make real improvements despite their size and despite being a bit behind the curve. They are doing it with Respecting for People and Kaizen: accelerating a virtuous flywheel—giving some air-cover for new approaches, engaging teams in designing the change, supporting teams doing the thing, and celebrating wins and lessons. Rinse and repeat.

How do you interpret the phrase continuous improvement?

What are you seeing?

I think this is an incredibly important piece, John. I share your observations and your frustration. There’s no question in my mind that at least a part of it is the tight intertwining of high finance and technology. That alliance has driven spectacular growth for some but at the expense of quality and sustainability for everyone else.

Toyota was forged under drastically different conditions than these. As was the Agile movement originally, developed at a time when tech was not considered as much of a critical part of the economy. Now Wall Street has a stranglehold on technology development and it shows.

But like you I have hope. I’ve seen many pockets doing work with compassion and integrity. We must seek out one another and raise the visibility of these examples wherever we can.

Everything comes in cycles of hype and bust. It’s been almost 25 years and everybody has almost forgotten the pains of death march driven delivery. That specter hasn’t gone away and as soon as an Org lets up without respecting the people doing the work, it comes roaring back.

We’ve been in a long boom cycle with Agile among other things and it’s only natural that there is a contraction.

As long as there is a death March there will be a counter against it that values ppl and doing things like CI. We just have to keep improving how the latter bits are great for business and longevity but it’s always a battle against short termism and ignoring of its externalities.