Help needed! I’m thinking of doing a cohort course. Can you help me hone in on a topic by completing this short survey? Thanks!

I'll always remember a leader asking me:

If things are so broken, why aren't we hearing about it?

I didn't have a great answer then, but now I do.

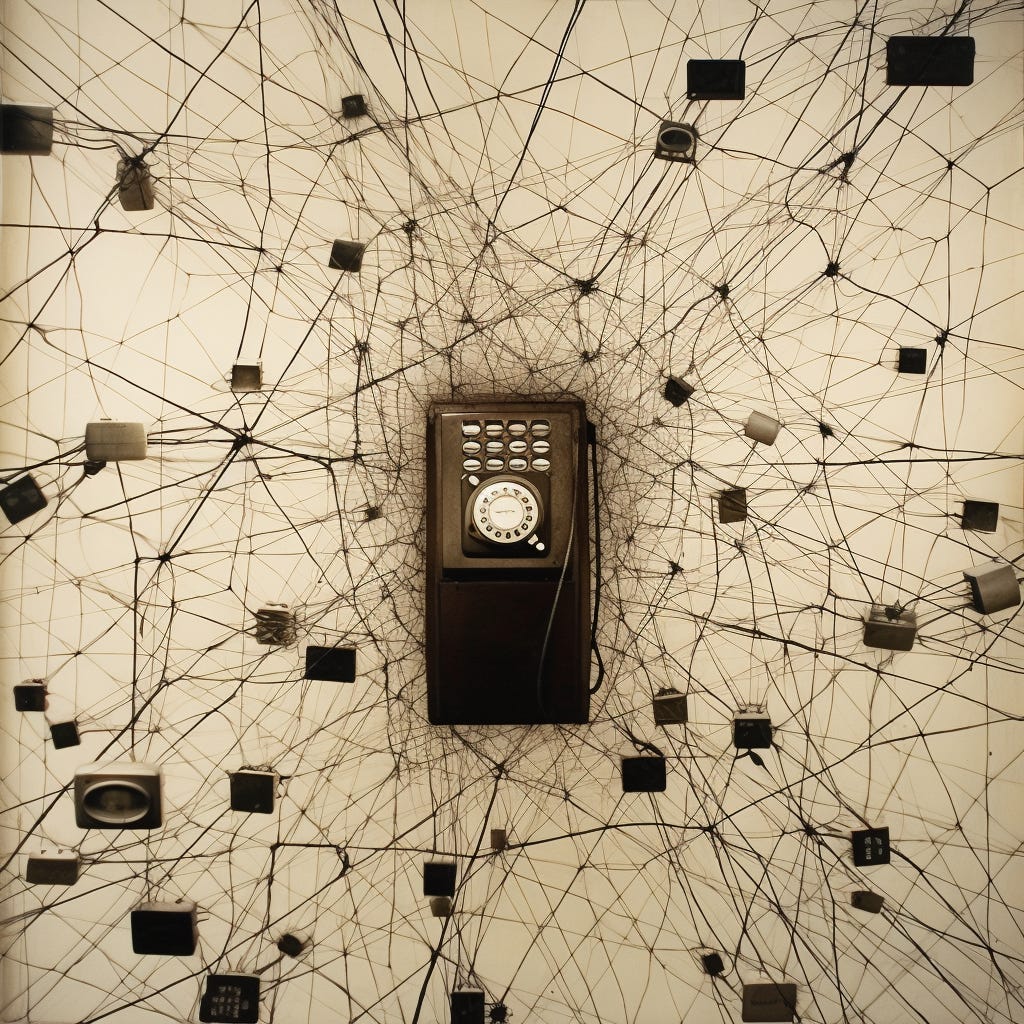

My theory is that many more people notice issues than raise issues—even in relatively psychologically safe environments. The more dysfunctional the org gets the lower the ratio. That—along with the fact that people choose to stay at/leave companies (survivorship bias)—means that it is very easy for leaders to discount certain things as fringe, rare, and unimportant.

To make things even harder, there tend to be always top-of-mind topics like "communication" and "time to focus" that dominate the feedback space.

Remember, someone might not speak up if:

They lack confidence. Intuitively they sense that something is off but are not confident in their ability to describe the problem, defend their perspective, or propose potential solutions. I'll always remember working with a new grad engineer. Their intuition was spot on when things could be better. But they assumed they were missing something (e.g., "Well, what do I know, I've only been doing this for a year.”)

They've tried unsuccessfully to bring up the issue in the past. At a certain point, people pivot to self-preservation and "riding out" work situations. They see the problem but have calculated the risk/reward of continuing to raise the issue and have concluded that the risks outweigh the benefits.

They assume the situation is normal. Based on their lived experiences, they see the issue as a "fact of life" or "just how X works," and any solutions are deemed "utopian" or "not possible in the real world." Of course, the flip side is true for people who have seen something work but haven't worked in environments where repeated efforts to make it work failed.

They know there is a problem but misattribute the cause of the problem. A classic example is that someone may notice poor communication between groups but fail to connect the dots between poor communication and a problem with org design. They provide feedback on "cross-team communication" (a commonly mentioned problem), and the input gets watered down.

They fear their job is at risk. Not everyone has the privilege of pushing back and calling things out. The next gig may be hard to come by in today's job market. People worry they may get on the wrong side of their manager if they keep bringing something up.

They haven't heard from other people with the same challenge. Imagine you see and feel a problem, but no one on your team sees the problem. At that point, it's tempting to write yourself off. But say you know the feedback of fifty other people from across the organization with vivid descriptions of the same problem. You might be more confident about bringing the issue up.

They assume there must be a reason why things remain unfixed. When a company has a lot of positive forward momentum (or lots of things are broken), it is reasonable to assume that there must be a logical reason why broken things have remained broken. This happens to new employees and long-time employees alike. The new employees believe they're missing an important detail. The long-time employees assume that they must be doing something right if they've survived this long without fixing the issue.

They don't want to throw someone under the bus. Especially in environments that tend to blame individuals when things go wrong, it is perfectly logical to assume that bringing up a problem will result in someone getting in trouble.

They "aren't paid to worry about it." It's not their responsibility. Perhaps it feels unfair to point out an issue (and take the risks mentioned above) when it's someone's job to fix the problem. While it's easy to typecast people who think this way as not being team players, it kind of makes sense: let the other person do the job, and if they fail, hire someone else.

They don't know how to bring up the issue. Not all organizations clarify how and where employees should share their observations, grievances, and ideas for improvement. Is it a "just tell your manager" environment or a "wait until the employee engagement survey" environment? The issue is very challenging when a person's manager may be directly involved in the problem.

They believe the issue is too big to be addressed. Some problems are so ingrained in a company's culture that team members may feel it's futile to try to change them.

They fear isolation or exclusion. Often, people worry that by voicing their concerns, they might be seen as outsiders, dissenters, or non-team players. Even if their job is "safe," this could greatly impact the quality of their work experience.

They benefit from the problem. If your job revolves around constantly fixing a problem, then there's not a lot of motivation around fixing the problem. For example, someone hired to manage dependencies probably won't advocate for fewer dependencies.

The lesson here is that as a leader, you can't rely on "people speaking up." While fostering psychological safety and inviting feedback is an important step, there are still many reasons why people may choose not to provide feedback.

For example, take:

They assume there must be a reason why things remain unfixed.

Are you encouraging people to question those reasons and assumptions?

Or:

They don't know how to bring up the issue.

Have you clarified how to bring up issues, especially those related to managers?

Or:

They lack confidence.

How do you provide that confidence? How do you encourage people to speak their minds even when unsure if they are "right"?

Or:

They haven't heard from other people with the same challenge.

Are you actively helping (or preventing) people connect the dots with other teams?

I'll end with a question:

Are you waiting for people to provide feedback in surveys or to speak their managers?If so, is that going to be enough? Go through the reasons above and make sure that you’re providing channels and help where needed.

Some variants:

- not having the full picture/information. You can only make assumptions, bring half a broken solution.

- no direct access to decisions makers. You can only talk to same level colleagues. Can be considered as gossiping, so not very enhancing.

- If, by some miracle, an ear is trailing, feedback can be heared and solutions applied. The rewards will of course go to someone else than the initial solution provider. Not very encouraging, especially when the situation last for quite some time. Especially when there is a quite big gap between people.

How well can people recognise "brokenness" in organisational policies and practices? People who have worked in multiple organisations have seen a lot of bad managers and un-designed practices, unskilful use of managerial fads, and legacy kludges. What makes you think people can pick out instances of "brokenness" from the ubiquitous background shitness of organisational practices?