TBM 17/52: Decision Making vs. Decision Understanding

Big thanks to @ChrisSpalton for the review and drawings!

Two anglers wade in a river. One-hundred meters from each other. They complete each other's thoughts. I cast here. You cast there. I move here. You move there. Rhythmic casting, retrieving, and wading, pool by pool.

"Did you see that ripple, over there," one angler says with a nod. "Yep," replies her friend (with a nod). They share a lot of knowledge and skills. They use the same words. They know about rivers, this particular river, trout, these trout, the seasons, the hatches, fly fishing, each other, and so much more.

Decision making is fluid and almost automatic.

A couple miles away two PhDs at The University—a sculptor and a molecular biologist—are working on a project. What's happening? They take long walks together to learn about each other's world. New connections form. The theory of everything! Momentum! Then a temporary roadblock. Turns out artists and molecular biologists (or at least this artist and biologist) keep different schedules and have different uncertainty-level comfort zones. Quick, a proposal to "keep things on track!" Scientists are good at proposals, right?

Alas, the artist has concerns and edits, and feels a pit in her stomach ("is this what I signed up for?") Motivation flags a bit. "Wait, are you still dedicated to this?" asks the biologist? Of course. More walks. More work. More collective sense-making.

Decision making feels painful at times. Stilted. Circular. But over time, a wonderful partnership forms (and wonderful art springs to life).

Hopefully.

There is no magic framework to operate like the two anglers. No magic metric. No template. No activity. The PhD students need to do the work and invest the time, curiosity, openness, dedication, and an open heart. The tough reality is that they also can't force it or rush it. No human has an endless supply of the kind of energy. Our bodies/brains can only take so much before needing to recharge and DO something. To let our synapses make the connections they need to make—reinforced by action and motion.

Sometimes we try and don't get there and have to try Plan B, C, and D. Heidi Helfand, author of Dynamic Reteaming: The Art and Wisdom of Changing Teams, shared this observation and wisdom with me:

When people come together in teams sometimes everything flows and it’s so easy. Like water in a river rushing along, moving around the rocks it encounters. Other times we bounce off the rocks and we might not even know why. But we get back together and press on and try to have a good life together at work. Sometimes I think it’s a combination of luck or something magical. When you have it you don’t want it to end. It’s some kind of chemistry.

Chemistry, work, mystery, and luck. And you can’t force it. That’s not easy. Do they teach mystery in business school? I’m not sure.

Drift and Understanding

Teams often talk about decision making challenges and what I call Decision Drift. Decision drift is when you decide something, but then your commitment drifts. Your team feels they are going back to the drawing board often. How are we supposed to fix decision drift? "Decide and commit!" Jeff Bezos tells us. "Identify the directly responsible individual!" says Apple. Run RACI. SMART goals. Roll out OKRs.

I've come to see it in another way. Teams (and framework makers) focus a lot of attention on making decisions, but not a lot of time on understanding decisions and each other. There's a void in shared vocabulary, and a void in their shared understanding of implications and assumptions. And even when teams realize the issue, there's only so much cognitive "capacity" available to do the hard work to close the gap. Like the PhDs, you can't rush it. If you try, you can make it worse (something I’ve learned the hard way). Working remote during the pandemic has only exacerbated the problem.

What might lead to decision drift? Why don’t people just call it out? Let’s focus on the humans involved, and their response to the situation:

Some people don't know what they don't know. They aren't sure about the implications of a decision. It seems fine, at least to them. My friend asks me, "do you want to go deep sea fishing?" That sounds fun! Get me on the boat. Two hours later I am seasick, chopping smelly fish guts.

Other people might have a sense that there are impacts that aren't being discussed. But they can't put it into words. It causes a slight discomfort. The discomfort is too small to motivate derailing the meeting. Example: you ask someone for directions and food advice in a foreign city. They seem knowledgeable but you have a hunch they didn't understand you. You don't want to waste their time, and they seem very generous, so you hear them out, thank them, and walk in the direction they suggested (but duck into an alley).

For some, their coherence "radar" is finely tuned. They sense the lack of coherence, and while they can't place it exactly, they sense the general vicinity. It bothers them, and becomes a bit debilitating. "I'm getting a funny feeling here I can't shake!" they remark. Queue up most horror movies to get a snapshot of this. No matter what they say, and no matter what they do, they can't shake it.

Perhaps it does not feel safe or worth it to “raise the flag”. The issues are clear, but sorting them out will involve energy you don’t have.

Or imagine a skilled deep-sea angler joins the two river anglers. Talking seems superfluous. Isn't this all figured out? Fishing is fishing. Can't we just fish? They spend their whole day shouting across the river and scaring the fish. Their friend feels alienated and quits fishing. Turns out fishing is fishing...but only at a high level. We routinely think things are more similar than different. Or more different than similar.

Someone might be very skilled at communicating to people who "know nothing" about their domain AND people who only know about their domain. That's a unique skill--the connector--but not representative of all cross-disciplinary conversations. Can they see that? Or do they approach all situations with too much confidence?

There are hundreds of variations here. It is a heady mix of prior experience, assumptions, energy levels, patience levels, and practice. And changing context: a decision may be “final”, but the conditions shaping the decision are constantly changing.

So what can you do about it?

How about goals and objectives?!

Goals may create some alignment. Seeing that point on the horizon is a start. But how you'll get there may be completely up in the air. The goal may be too lagging to feel actionable. Or too leading to feel flexible and accommodate the skills/expertise of the people involved.

Or the team manufacturers certainty for the purpose of setting a clear but overly generalized goals only to have the uncertainty creep up on them. Remarks Jeff Eaton:

[One reason for decision drift] is that in the face of uncertain futures, we build "account for everything" systems instead of flexible playbooks. This is a big issue when planning for rapidly changing/uncertain future needs; "predict a path and build for it," breaks down easily when the prediction isn't exactly right.

So yes, goals can help prevent decision drift. But they can also cause it. And at the end of the day a goal is a placeholder for tons of background and conversations. It is shorthand. It is a construct.

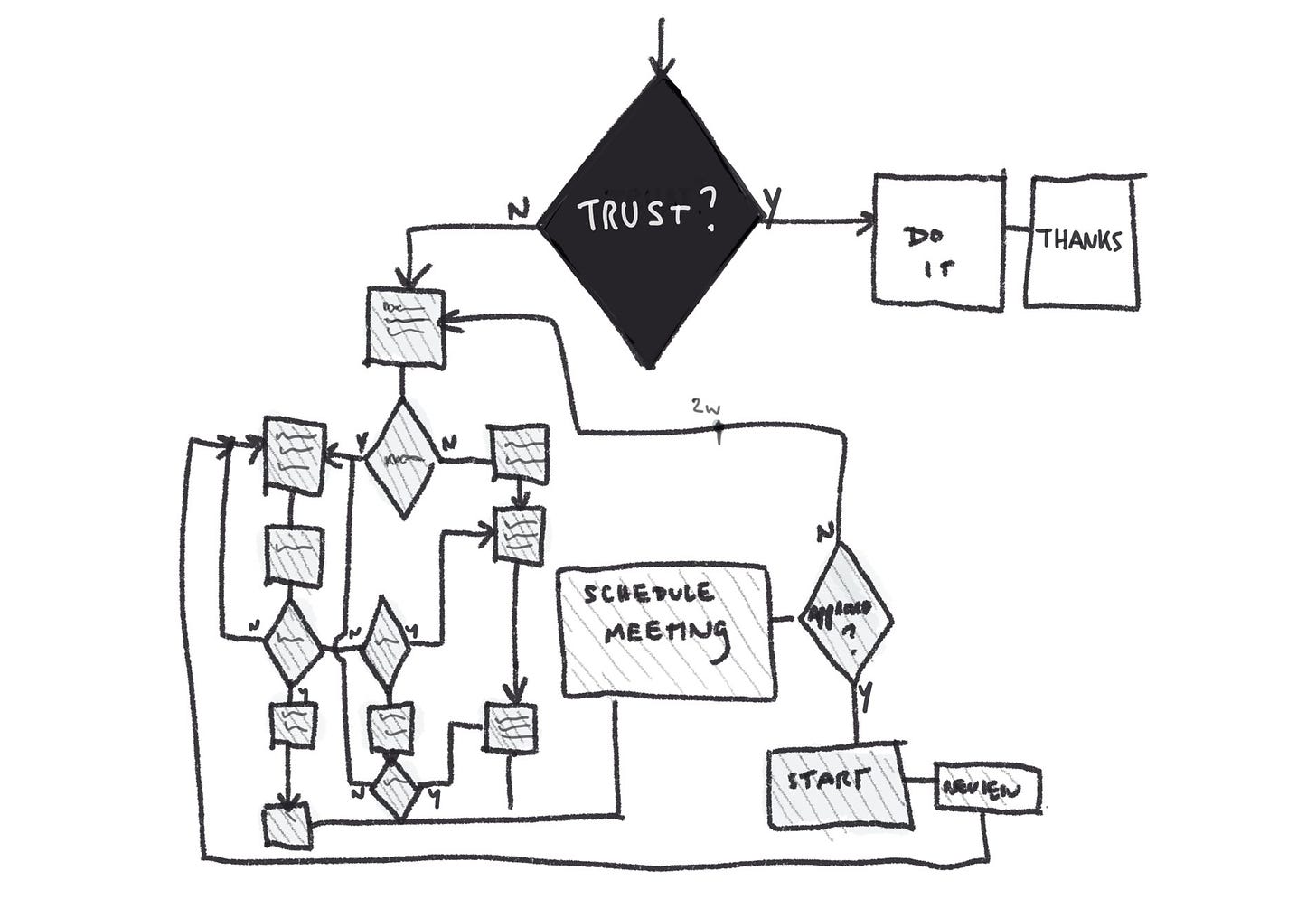

How about trust?!

A couple years ago I posted this image on Twitter. I believe in this message (and people seem to like it), but there’s more to it.

Teams often point to trust, and trust IS an issue in some cases, but I'm not sure it is that simple. Unless we create a highly transactional hand-off (e.g. "you do exactly X" and "I will do exactly Y") there will be drift. Things will happen that we don't expect. So perhaps it is less about trust, and more about decision boundaries. When we talk about trust, in many cases, what we are saying is:

Fishing friend. YOU stay in that POOL. OK?

Biologist! Send me the final rendered drawings of the cells, and I will create the sculpture!

If you stay in your lane, and I stay in my lane, and we each do the thing the other person can't understand, and we combine our stuff, we'll be good!

Congrats! You are the trusted, directly responsible individual.

Unfortunately, this way of working is much better suited to complicated problems, not complex problems. The trust we seek—if we even call it that—is not that easily attained (and not something we can will into existence). It certainly isn’t a “just”: “we just need trust!” Faith might be a better word actually…or trust in best intentions and our collective ability to work through it.

In other words, we may actually want and need the friction of the Trust=No route, albeit with the requisite safety and trust to work through it. At least at first. Our team may also behave as if “people don’t trust each other”, when mostly they just don’t understand each other. “We all care about psychological safety, and making this safe for each other. We just haven’t figured out how…yet.”

OK. What then?

Amazing things can happen when people from different disciplines work together. This approach is especially important for complex problems that benefit from diverse perspectives.

There's no magic framework that can instantly solve the problem. People require time to process—alone AND together.

They need safety to challenge their own assumptions and the assumptions of team members. To explore and dig. In our day-to-day, there is so much pressure to decide quickly. The end result is that premature converge makes decisions fall apart.

You need bandwidth and you can't rush it. When we rush to a plan, a goal, the RACI...what we are doing is creating PROXIES for understanding. Sometimes this will produce short term outcomes, but it is rarely what you need for lasting results.

Take a break. Come back rested.

Work through professional culture clash.

Experience can help, but so does a beginner’s mind. If you’re very experienced, keep in mind that it might take a long time for people to catch up.

You need “doing”. Talking doesn't help after a certain point. It is important to shift your approach and change things up. Wade the river. Draw a molecule.

Tl;dr

Decision making is part “the making” and mostly “the understanding”.