Two questions jumped out in the last week. First a DM:

John, I don't know what it is, but your writing has changed in the last few months.

And second, a reply to last week's post on the current puzzle in tech:

This is a very insightful post that nails many dynamics happening today. I am most fascinating by the fact that nearly EVERYONE would agree with this, and all the comments you include show that we clearly know things that can make this better, and yet......it so seldom happens. Why?

My answer to these questions is related. This post is about how I hit a mini-crisis of awareness and worked to expand my view. Yes, my writing has changed a bit and has probably pissed off the "Stick to product, buddy" crowd. Apologies!

I'll use words like "political," which will undoubtedly make some people nervous. Stick with me, or perhaps skip this one if that's you. Spoiler: This post is about how models we take for granted are seriously tested when the social contract—real or imagine, or both—dissolves.

Mission Command

Tech companies, in particular, and modern companies generally use organizational structures and operating models that closely resemble military organizations.

Hierarchical structure, chain of command, boundaries of decision-making authority, etc.

A mix of specialties, sometimes working alone and sometimes working together.

Control systems: detecting and responding to variability, escalation protocols, "mission command," and "management by objectives," etc.

Emphasis on leadership to guide, inspire, make hard decisions, motivate

Emphasis on "management" to coordinate, motivate, escalate, and "execute."

Startups are slightly different; think pirates, Seal Team 6, covered wagons "heading westward," expeditions, and privateer fleets. But the models—companies and militaries—converge at any meaningful scale.

Andy Grove, famous for his work at Intel and often credited with developing the prototype for Silicon Valley operating principles, advocated for many practices that closely aligned with the military mission command doctrine. Replace "Airmen" with "Teams" in the following quote, and you could be talking about a good chunk of all business books:

Mission command is a philosophy of leadership that empowers Airmen to operate in uncertain, complex, and rapidly changing environments through trust, shared awareness, and understanding of commander's intent.

If you're interested, Stephen Bungay's The Art of Action is a helpful follow-up book.

Tech companies (especially big tech and the Silicon Valley ecosystem) and militaries have two other things in common.

Apolitical. They work hard to describe their environments as "apolitical." Political maneuvering is seen as a threat to an espoused need for speed, operational effectiveness, and innovation. There's little appetite for the social science view that politics exists anywhere where power, influence, diverse needs, and interests are in play.

Meritocracy. They put significant emphasis on merit and ability. "The Few. The Proud. The Marines." "We only hire A players." The expectation is that the higher you get in the org hierarchy, the more exceptional your competence and leadership should be. Like politics, there's zero appetite for imagining how and why meritocracies might not exist other than the self-confirming argument that politics and bureaucracies might "break" systems that rely on merit. Remove politics, add situational awareness and transparency, and you're back to a meritocracy (in theory).

The general idea is that mission command works when 1) information—the "ground truth"—can flow freely up, down, and across the organization, 2) when you're hiring qualified individuals who can be "trusted" to work independently and use sound judgment, and 3) when leaders are skilled at communicating "commander's intent."

I remember, up until a couple of years ago, the degree to which I equated many of these ideas to some sort of unassailable vision of how work could and should happen and why it was good for humans. The principles rang true on a deep level, even if, personally, I trended a bit more collectivistic. They were self-affirming and felt humanistic and optimistic.

"If we could just figure out how to empower teams, circulate context up and down the organization, and face reality, that would allow these creative makers on the front lines to do their best work and help humans in the world!" I'd think to myself repeatedly.

But that view has been slowly shifting. To explain how I need to tell you about a book.

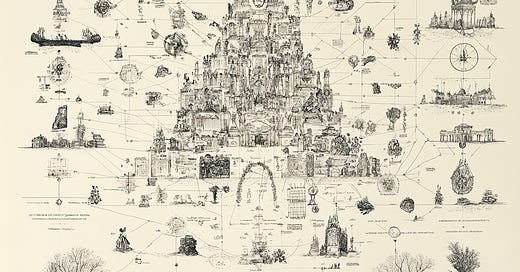

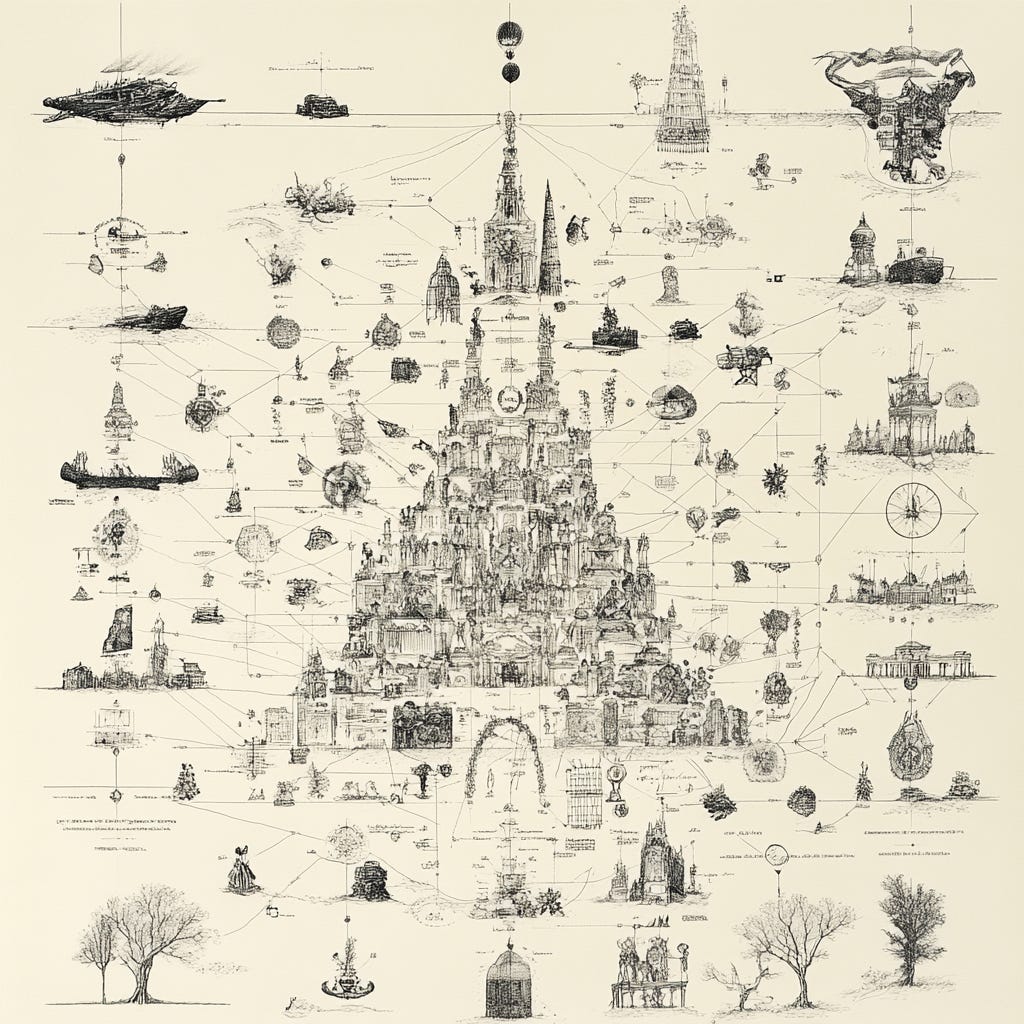

Images of Organization

I picked up Garreth Morgan's Images of Organization about a year ago. In the book, Morgan invites the reader to explore different frames (images) of organizations. They included seeing organizations as:

Machines

Organisms

Brains

Culture

Political System

Psychic Prison

Instrument of Domination

Flux and Transformation

Each metaphor has its pros and cons. For example, seeing an organization as something that is finding its place in the "fitness landscape" (Organism) has the advantage of understanding how organizations partner and compete for resources but fails to capture the internal dynamics of power and influence (Political System).

One of my huge takeaways from the book is that it is popular to criticize things like Taylorism and the machine-like view of companies as not being a good fit for knowledge work, but at the same time, have blindspots and frames we unintentionally or intentionally favor or avoid.

"Why can't the leadership team understand queueing theory or the theory of constraints?" asks the exasperated Lean/Agile change agent, without considering the cultural frame that might favor the idea of individuals as rational and competent judges of their work in progress. The same thing happens in reverse, of course, when the "culture eats strategy for breakfast" person shows up and imagines all things can be explained through the lens of cultural norms and values while ignoring things like the raw impact of context switching and juggling threads.

Reading Images of Organization was a turning point for me as it was a kick in the butt to challenge my default frames. This brings us to the political frame, with a smattering of culture and instruments of domination.

P…P…P…O…

In several recent posts, I have discussed the current industry climate as one of "asymmetry." People—executives, investors, upper managers, middle managers, and front-line contributors—are experiencing very different realities and, in turn, are generating and circulating very different narratives.

These narratives range from CEOs claiming everything is fine and dandy; they're all in on AI, and whoopsie that suddenly means that 10% of the team is underperforming, to front-line UX Researchers wondering if they should just jump ship and become product managers. Some people are enjoying the spoils of generational wealth amassed in the last decade and a half—angel investing a little here and there and doing some fractional roles—while former design leaders are wondering if they'll ever get a job in tech again after spending multiple quarters unemployed.

This week, we witnessed a classic exchange between Eric Schmidt (former Google CEO and big fan of Grove's High Output Management) and the Alphabet Workers Union. When asked why Google was falling behind in the AI race, Schmidt told students at Stanford:

Google decided that work-life balance and going home early and working from home was more important than winning

The union fired back:

Flexible work arrangements don't slow down our work. Understaffing, shifting priorities, constant layoffs, stagnant wages and lack of follow-through from management on projects - these factors slow Google workers down every day.

Who is right? What is real?

What is clear is that we are NOT dealing with a singular narrative or experience. There is no common "enemy." Companies don't have a singular culture. In many ways, we are fighting each other or at least pushing back on competing and opposing narratives. In countless conversations with friends in the industry, there is a pervading sense of decreasing company loyalty and increased questioning of the core tenets of working in tech.

A big contributor here is layoffs.

Despite efforts to convey otherwise, layoffs, in particular, are overtly "political" endeavors if we define politics as the negotiation of power, influence, and competing interests within an organization. In What Companies Still Get Wrong About Layoffs by Sandra J. Sucher and Marilyn Morgan Westner, the authors make two bold claims:

Research shows that layoffs continue to have detrimental long-term effects on individuals and companies.

Layoffs negatively impact companies in real but hard-to-measure ways.

Sucher and Westner explain the asymmetry regarding "dispersed" (hard-to-measure) impacts.

The breadth of these effects explains how post-layoff underperformance happens — and how it can be missed, since the impacts are dispersed throughout the firm in activities and functions that might not appear at first to relate to layoffs.

This view is heavily grounded in behavioral economics, expected utility theory, and the impact of information asymmetries. It implies that layoffs would be less common if the impacts were truly measurable. There's another view: that layoffs have little to do with expected long-term "utility" and much more to do with power consolidation, cultural and political reorientation, optics, etc.

To quote a friend who has had the unfortunate privilege of observing far more of these situations than I have:

It seems like as soon as you pop your head above a certain level in the hierarchy at a company, you have to be ready to hear some real antisocial comments, like blatant politicking and actively cheating employees.

I have no basis for claiming my experience is representative. Still, it makes me dubious that people act like role elimination is the outcome of a measured, reasoned process and is, therefore, evidence that certain roles are not "needed" across the industry.

My experience has consistently involved a messy, chaotic process of putting together "the list," which invariably includes people who just annoyed the wrong VP by talking back. Or the vague "not a culture fit" claim that seems to amount to some kind of homogenizing fascist impulse.

No exaggeration, it's the XXth time in XX years I've found myself at the center of a [RIF], and they have all been vindictive and abusive and repulsive.

The big point here is that:

Whether we want to admit it or not...

Regardless of why we think it is happening, who (or what) is to blame, etc.

Whether we see whatever is happening as an age-old phenomenon or something unique to the times…

Regardless of what we believe will "solve" the problem or improve the situation

…we are navigating divided times, or at least times more divided than connected. Some people are responding by seeking to purge out diversity and seek homogeneity. Other people are seeking to build more bridges and more shared understanding. Either way, it is there.

Like the newsletter? Support TBM by upgrading your subscription. Get an invite to a Slack group where I answer questions.

Back to Mission Command

Here's a hot take.

Mission command works when some sort of social contract or binding narrative exists. Mission command works through "trust, shared awareness, and understanding of the commander's intent." When that contract breaks, mission command breaks.

In the 1917 Revolution, Russian soldiers became disillusioned with their leadership due to massive casualties (World War 1), poor conditions, lack of supplies, and a disdain for the aristocratic officer clash that was out of touch with the realities on the ground. There were widespread mutinies and the eventual collapse of the army's ability to function as a coherent force. Similar things happened with the French army during the Napoleonic Wars (1812), with US forces during the latter part of the Vietnam War, and with the British Army in the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921).

"A house divided against itself cannot stand." – Abraham Lincoln.

Whatever "contract" existed (again, noting that this contract likely privileged certain people, etc.) is eroding. Contracts are always eroding, so this isn’t an especially astute observation. But it is till worth mentioning.

Let's consider the way escalation works in an idealized mission command setting.

Problems should be resolved locally whenever possible (hence the focus on empowerment and pushing decision-making down to the people close to the problem)

Leaders maintain a clear overview of the performance of their respective teams and units.

Issues that cannot be resolved locally are escalated through the chain of command to more competent and powerful people.

To function effectively, teams must be competent and must focus on the greater organizational good rather than politicking, obfuscating, or spinning.

(I highly recommend Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders by L. David Marquet for an inspiring take on escalation in a supported and empowerment-rich environment).

But imagine what happens the minute there is any sort of distrust, questioning of motives, or political divisions. Imagine what happens the second experienced people in your company decide to lay low because:

It isn't worth raising issues.

Working together is hard.

The job market is tough, and other companies are likely "just as messed up?"

Imagine what happens when a leader gets a bug in their ear that people are slacking, that "hungrier people are out in the job market."

Information doesn't flow.

The team which spends 80% of its time wading through debt, feels pressured to publicly state that the number is 20% and that it can take on new work.

People don't bother passionately raising the flag on the CEO's proposed strategy.

Teams try to solve the same problem in different ways to avoid conflict.

Success theater. Everything is FINE!

Leaders task managers with spending more time "in the details."

In short, mission command works when there is an overall sense of integrity, representation, and legitimacy in "the system." It doesn't matter how your OKRs flow, when you have reviews, how you structure your organization, etc.

And with that, I've hit my time limit for the week. But I will write a Part 2 if there is sufficient interest. I have thoughts. For now, I recommend this post by Heather Stephens to explore legitimacy in organizations. A teaser quote:

As mentioned, legitimacy is not binary—no authority structure can ever be perfectly legitimate to 100% of its constituents all the time. Conditions change, and communities of people are complex. As a result, some regimes are more legitimate, and some are less, but gaps always exist.

UPDATE: I did a Part 2 based on the poll below.

Like the newsletter? Support TBM by upgrading your subscription. Get an invite to a Slack group where I answer questions.

I studied with Peter Drucker in the late 90's and he pointed to two things that he said would irrevocably rock the employer-employee relationship, and have massive ripples across society at large: 1) executive/CEO compensation:average employee wage ratios and 2) layoffs. Where we are now is so far beyond what he predicted I often picture him rolling six feet under.

From The Drucker Institute:

"Drucker had seen firsthand what happens when society stops functioning, having witnessed the rise of the Nazis in the aftermath of the Great War and Depression. This was the central theme of the first of the 39 major books – The End of Economic Man – that he would publish throughout his extraordinarily long and productive career. “These catastrophes broke through the everyday routine which makes men accept existing forms, institutions and tenets as unalterable laws…They suddenly exposed the vacuum behind the façade of society.”

Drucker was determined never to let things break down like that again and set out to help leaders build effective and responsible institutions, learning much from rising corporate leaders, which helped inform the writing of some of his most popular books – The Effective Executive, The Concept of the Corporation, The Practice of Management."

One of your best pieces!